| |

|

|

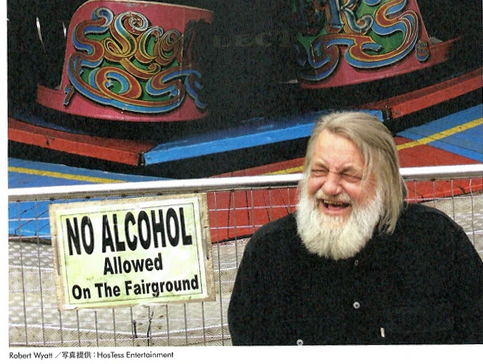

Robert Wyatt: the Matching Mole interview - Popgruppen - January 28, 2019 Robert Wyatt: the Matching Mole interview - Popgruppen - January 28, 2019

In celebration of Robert Wyatt’s birthday, we here republish an interview with Robert focusing on Matching Mole. This is a pretty long piece, but rather interesting too, I would say!

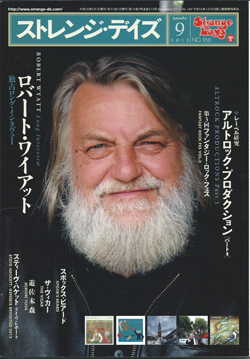

The article was written by Michael Björn and originally published in Japanese music magazine Strange Days #166, pages 14-25, September 2013*.

Copyright © Michael Björn 2013

* Please note that this is the original English article manuscript submitted for publication, and eventual differences to the Japanese translation made to make the article fit in the allotted space are not accounted for. |

|

| |

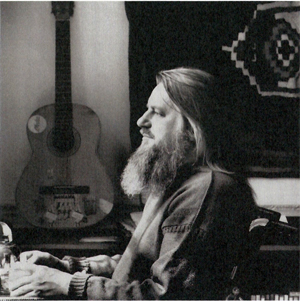

The first time I interviewed Robert Wyatt was in my late teens. I was invited to his London suburb home and was totally overwhelmed to meet this great rock star who had carefully prepared the visit with a selection of Swedish jazz records. For me – a teenage school kid. He has remained a great hero ever since, musically as well as on a human plane.

However, when I contact him about this article, I get a categorical refusal and a ”No more to say.” Period.

Robert is very unhappy about how recent reissues have heaped bonus tracks on the originals. And just like he sings on ”Gloria Gloom”, he still has his ”doubts about how much to contribute to the already rich” – in this context represented by the record companies.

But during the course of some e-mails, Robert thaws and agrees to the interview. I get the feeling that his frustrations are overcome by a warm pride over the original albums, unique and masterly as they are. The last few e-mails are adorned with rhythmic references, a ding-ching here and an oobop sh’bam there. When we finally hook up, Robert is in a very good mood, full of friendly laughter. Again, I feel like that teenage school kid, totally charmed by his kind and thoughtful attitude. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

My idea is that I would like to do an interview and send you the text before we publish.

Robert: You said that before. I don’t like the idea that I would have any kind of censorship role. I will tell you whatever I think and you write whatever you write.

OK, fair enough!

Robert: You should, however, be clear that it was your idea to talk about these things. There’s a joke about a bishop who arrives in a city and a journalist asks him: ”Are you going to visit the red light district in our city?” The bishop replies: ”Is there a red light district in your city?” And the front page of the newspaper the next day is: ”Bishop asks: Is there a red light district in your city?”

So, I would like to talk about Matching Mole and that is my idea then and not yours!

Robert: Yes, that’s right, ha ha!

Matching Mole is a pun on the French translation of Soft machine, ”machine molle”.

Robert: Yes, that is what the French call Soft Machine. So I just thought I’d carry on with that. I didn’t see why I should lose the name completely.

When you were in France with Soft Machine, they actually called the group ”Machine Molle” then?

Robert: Yes, they did that anyway, so that is my little joke, that’s all. Nobody owns the name, so in fact anybody can call themselves Soft Machine. I thought it would be quite funny to just call the Matching Mole records Soft Machine 5, Soft machine 6 et cetera and so on. But then I thought: ”Oh, never mind, I won’t do that.” He he he!

How did the band come about, originally?

Robert: I can’t remember… I can’t remember how I knew Bill MacCormick. He knew me because he was a school friend of Phil Manzanera, and they used to come to Soft Machine concerts, apparently, when they were young. But apart from that, I don’t really know. Dave Sinclair I knew from Caravan of course. And Dave MacRae, how on earth did I hear Dave MacRae? … I can’t remember, that’s ridiculous.

I started earning a living from music about 50 years ago. And for about ten years, I was working live, playing drums non-stop just every day. From 1973 until now obviously not on drums – but there’s been so much stuff, it is hard to remember.

How did you approach making music with Matching Mole?

Robert: As a child, the music I listened to was my father’s music, classical music basically. Then my big brother came home with his jazz records, and the LPs were pretty long too. I got used to that… in fact, to me, the innovative thing to do is to make short songs of three or four minutes, like pop records. I wasn’t interested in if they were commercial, but just the idea of completing a piece of music in two or three minutes. It is the opposite way around, I think, from a lot of what people call progressive musicians do. They start out as rock musicians and then go on to do grand works afterwards, you know.

So the progression is in the other direction, from long to short.

Robert: It is in the other direction. It is interesting where we meet, but I wasn’t going that way. And to me, the dramatic discovery in the 50s was pop music. I had never listened to it as a child. So I thought ”Well, that is really interesting! You just do a song and stop after three minutes, wow!” Ha ha ha!

Ha ha!

Robert: My dad had things like Hindemith, Stravinsky stuff and Bartok. To me that was how long music was. And then my brother had stuff like Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Gil Evans, which were quite extended sort of things. So that was how I started thinking about music. It wasn’t trying to be clever.

I didn’t like the fact that people thought very carefully about the beginning to get people listening, but they would put the weakest track at the end. In fact, I think that the impact of a record ending is as strong as a record beginning. The last notes of a record – just like it did with a symphony – that’s the thing that is hanging in the air when it stops.

About the first Matching Mole record

Even though you are going in the other direction, on the first record you don’t end with the pop song ‘O Caroline’, you start with it.

Robert: No, I hadn’t gotten around to that yet. But often I would play Dave Sinclair’s advocate. When I was with people who looked down on pop music, I would be very defensive and say: ”Well, you try and do that. It is not so easy.” But when I am surrounded by people who think anything that isn’t pop music is just pretentious and boring, that upsets me too. I don’t see why there had to be battles. Instead one should enjoy the differences.

How did you go about putting the music together?

Robert: We lived in a place called ‘All Saints Road’ – a short attempt of having my own place, it was disastrous. But we had an upstairs and a downstairs – and downstairs, we had all the instruments. It was a very run down, poor area at that time. We could make a lot of noise and there weren’t any neighbours who would make a fuss so that was OK. So there we were.

And really, it was about playing. Like jazz, it is about playing instruments as opposed to anything else. I wanted to reverse the process that happens in jazz, whereby you start with a plan but the improvisation is sort of the last thing.

On the first record we used themes, mostly by Phil Miller and myself: not songs or tunes really, just kind of patterns. But there can be endless variations on how to deal with these patterns. You keep the rhythmic pattern going or the harmonic pattern, and everything else changes. It was very influenced by free jazz, but I wanted to be based on a kind of rock sound. I wanted that kind of freedom in a rock context and I think that was what was unusual at that time.

The thing is then to turn it into something, and that is done in the editing of the recording. We would go through the routines for hours, but the process was to find the ones were it all kind of worked coherently, and to throw away all the bits that didn’t work. That is what upset me with the CD reissue of this record. They put in all the stuff that didn’t work with all the stuff that did work. And I feel… that it upsets me, frankly. Because although the original LP may sound random to a casual listener, it is not.

I really like things to sound as if people have just thought of it and it is totally easy and they don’t have to think about it. What we call ”artless”. I like artless art. People think it’s random; it is not random. There’s a nice quote, I think it is Cezanne: ”People think my paintings look as if they are done too quickly. That is because they are looking too quickly.” Ha ha ha!

I suppose you want to put musicians in situations that they are not accustomed to, in order to make them grow?

Robert: It is more selfish. I want to hear music that I have not heard before!

I think Dave Sinclair really did feel that he was in a different context than he was used to.

Robert: He was uncomfortable; he wanted to do straightforward songs. He would be quite happy doing that and he does it beautifully. Personally, I found that he was a lovely improviser but it made him so anxious that I couldn’t to it to him after a while. Nobody would let him down a groove; Bill didn’t lay him down a groove, and I didn’t lay down a groove. Phil chooses completely unlikely notes on guitar, there’s absolutely no telling what notes Phil is going to play, or when and where – and Dave was completely unnerved by it, I think. Nevertheless, he did some terrific stuff on the album, and so I am very happy with that. We were very good friends, you know, he didn’t have to do it. I don’t think he regrets the experience, I hope he doesn’t.

Dave Sinclair told me that you called him back from Portugal. You had really decided that you wanted to have him in the group?

Robert: Absolutely, I knew some very good organists like Zoot Money and so on, but on the whole, the keyboard players I knew were either jazz players or jazzy blues players – which is a wonderful thing, but it is an idiom that exists already. Or, there were marvellous keyboard players who worked from a classical tradition who were interested in improvising. But I found that they had not a very strong concept of what I considered as swing or groove at all.

So there was difficulty finding musicians to play with. I didn’t want people whom you can identify as belonging to any particular idiom.

I didn’t get these certain ideas from music first; I got them from paintings. Bonnard is nothing like Degas and Degas is nothing like van Gogh and van Gogh is nothing like Kandinsky. They don’t seem to be trying to fit into a… thing. They are developing their own… language. And I just wanted people who would do that and not just think: ”Oh, this is a jazz thing” or something. I was really looking for something that hadn’t been done before.

About ‘Little Red Record’

|

|

On ‘Little Red Record’, the other musicians have a bigger role in the development of the music.

Robert: That’s right. They were more familiar with each other, and they were more familiar working with me, so they knew what they were writing for.

This also means that ‘Little Red Record’ was more ramshackle because, although the playing on the first had been democratic, I had been totally autocratic on the editing. I felt that on the next record we made, I really must let everybody else do his thing. Whatever they want to do. So Dave MacRae does tunes, Bill MacCormick does tunes, Phil Miller does stuff and so on. By its very nature, it is less coherent in that way.

The title seems less ramshackle…?

Robert: It is not seriously political, although people think it was. I wasn’t particularly interested in politics at that time, it was just my joke, you know. Everyone thinks we mean the little red book, but it could easily mean ‘Little Red Engine’ which is the name of a children’s book in England, about a train.

There was some very simplistic socialist rhetoric on the record. I have no idea if I meant it; probably I had no idea what I was talking about. But the idea of the imitation Maoist cover was entirely the record company’s, not mine. Nothing to do with us. And I would be embarrassed about that cover because poor Dave MacRae who’s the gentlest man in the world has been given a frightening looking gun, which is very unfair on him because he wouldn’t hurt a fly.

Some of the songs are nicknames.

Robert: Yes, if anybody is interested in those things ‘Gloria Gloom’ is my Alfie and ‘Flora Fidgit’ is Julie Christie, the actress.

And together with Dave Gale, they are Der Mutter Korus.

Robert: Absolutely. I only met Dave gale again recently, he made films and so on. In fact, it was he who was a friend of the Pink Floyd. When I broke my back, it was he who said: ”Why don’t you do a concert for Robert?” So I have lots to thank Dave for, he is a friend of Alfie’s from, I think, art college.

Alfie and Julie are both talking on the record.

Robert: That is true. Then again Dave Gale is on there. He is making very funny little things, if you can hear them, about wanting to wear his woolly. He always likes to wear his woolly; it makes him feel more secure; some strange neurotic stuff. Julie for some reason decided to become a prostitute with a first-time customer. And Alfie wonders what on earth they are talking about. Anyway, we kept all of it on there. We really had good fun with that.

It seems that Julie’s first-time customer is a woman?

Robert: Yeah, that’s an implication there; Dave Gale certainly is not interested is he? He is too busy with his woolly. But really, I don’t think it was thought through, I think they were improvising as much as musicians do. Then again: in a way that they would never normally do. It was very interesting and fun to try and work out how to keep instrumental coherence and allow some of the voices to come through, but not always.

Given that the record is a bit chaotic, Robert Fripp seems like an unlikely producer.

Robert: Yes, I know! I think he didn’t quite know why I asked him. Funnily enough my son came over yesterday, he had found a photograph of Fripp and me, at some festival I think, talking to each other. It is a very merry little photograph and I don’t remember it at all. I don’t remember listening to his band or him listening to mine, or anything. When we were working in England in -67, there weren’t really any other bands that I knew out there.

Phil Miller found it difficult to record in the studio, since he was in awe of Fripp.

Robert: Yeah, Bill MacCormick mentions that. Phil is in fact always like that. He is almost chronically shy and never seen in person. But if that was the case, I am ashamed to say I didn’t really notice. I had been on the road with Hendrix, so it was very hard for me to imagine being awestruck by the presence of a terrific guitarist after a year of that.

Brian Eno is also on the album.

Robert: Yes, that was because Bill MacCormick knew him since he was a friend of Phil Manzanera’s. Bill asked him for an introduction to ‘Gloria Gloom’, but he did it in his own studio and just brought it in and we worked it into the thing.

He did bring his synth into the studio, I think Dave MacRae is using it on the record as well.

Robert: Yeah, that is possibly quite right. I had completely forgotten that! Yeah, that’s right. Eno contributes to the record in a way that is so discreet you often don’t know he is doing it. Dave MacRae himself is very inventive on keyboards, using the fuzz box and pedals in a kind of crazy way anyway. But certainly, he would be very happy for Brian to be trying stuff.

There was a CD release of ‘Little Red Record’ on BGO in 1993 where the A-sides and B-sides where switched. I read that this is the way you originally wanted the album to be.

Robert: That is true. I wasn’t sure about that. In the end I decided that it meant starting the album with Brian’s introduction to ‘Gloria Gloom’ basically. And I thought it took too long to come in. And I thought: “Get some food on the table” you know.

Ha ha ha!

Robert: So I abandoned that after a while. I had exactly the same idea when I did ‘Ruth is stranger than Richard’, I swapped the sides around on different versions.

You were thinking loud about the track composition so to speak?

Robert: I was, yeah. I took responsibility for that because… somebody had to. I didn’t really know anybody, not even Fripp, who was thinking like that; every track in terms of the complete piece of music, where it was in it and so on. Which is always a thing I like to think about.

Comparing ‘Matching Mole’ and ‘Little Red Record’

The two Matching Mole records sound fundamentally unlike each other, how did that happen?

Robert: For the ‘Little Red Record’, I decided for some reason in my head at that time, that I would play without a snare on the snare drum all the way through. If you take the snare off, it doesn’t just affect the snare drum, it affects the bass drum and it affects the rest of the band. It makes it more kind of translucent, if you like.

The moment you have the snare on, it affects the bass and you get those thumps without notes: boom-da, boom-da. The moment you take that off, a lightness comes through. Dave MacRae’s playing is full of light, and I wanted that. It is not rock & roll, it is much more fluid. I wanted to play drums more fluidly to see if I could stick with Dave when he was playing.

The other thing is, I like to try and have sustained pieces so that one piece flows into another and it is some sort of journey going through. That is consistent on both albums, but the thing which is different is that Dave MacRae came with his tunes, like that lovely ‘Smoke Signal’ thing, and Bill came with his rather Soft Machine influenced stuff.

For the first record, CBS was closing their studio and you were the last band in there – and then on ‘Little Red Record’ you are actually more or less the first band in the new studio.

Robert: Yeah! You know, I had forgotten that, you are quite right! Poor Dave Sinclair in that cold studio, I had completely forgotten that. But you know, even so, it didn’t influence us much. When you are young, you can sleep in fields you know. Ha ha ha!

With it being so cold in the studio, you had developed all the musical patterns before you came to the studio then, I suppose?

Robert: Not necessarily, because it is recorded and we didn’t record at home. So I think it must have been quite a lot of it trying out stuff in the studio. We did rehearse it for ours to get everyone familiar enough with the patterns to not have to think about them.

|

|

I used to prefer the first Matching Mole record because it sounds more like other Canterbury records. But the more I listen, the more I like the ‘Little Red Record’ because it doesn’t!

Robert: I have exactly the same reaction! I have been listening to them since you got in touch. The first one is totally coherent; I understand what we are trying to do and we did it. The second one is much more reckless, but because of that I find it very interesting. And I don’t mind hearing the variations, the different takes, because they show different aspects.

In the case of the CDs, definitely it is the CD of the ‘Little Red Record’ that has more listening stuff on it. I am more comfortable with it now. I completely agree: I reversed on that. On the first one, I am very unhappy with the extra tracks and the repeats of the single and, I don’t know, I just find it’s a mess.

So yes, I agree. It is exactly what happened to me, listening to them.

About reissues

You are obviously not happy with the Matching Mole CD reissues.

Robert: I really like the idea of two sides, whether is on the original 78 rpm records or eventually on vinyl LPs. And I always find it very interesting that there are two sides on an LP of about 20 minutes each. This sounds very pretentious and I am very pretentious, mind you, but I find that a lot of life is about two unequal halves. Just the fact that so much is binary: eyes, arms, men and women, everything. If you watch a sprout growing, very often the first thing you see is leaves alternating one side and another, they are not quite the same.

I like the idea of one side of a record being about the same thing as the other side but quite different. There is no literary equivalent, I can’t say this in words, I just have a feeling that the A-side and B-side meant something to me. Particularly on the first Matching Mole record but then again on the later ones, on ‘Rock Bottom’ and ‘Ruth is Stranger than Richard’. Even when it became CDs, I tend to divide things in two parts at least. To have different parts, whatever kind of shape, parts that are about 20 minutes long, that seems to be a good length for listening to a piece of music without having to go and have a piss or get another drink or something. So that was the idea here.

But there again, I am not happy with putting them all together in a big lump, because I want to make records that you can leave on until the end. If you make records where you have alternative takes, the same thing again and so on, it is OK for archives, for historical record, but it no longer serves the original function: A record you could put on and leave on until the end. So that was the idea of the original thing.

Live performances

You managed to play quite a lot of live shows during the short lifespan of the band.

Robert: We did, yeah! And they were very good fun to play. I used to like changing the themes, like… on the original ‘Marchides’, Dave wanted the improvisation completely out tempo, rubato or whatever the word would be, and I wasn’t comfortable with that live. So I started to put some sort of a pulse underneath it. As much as I love free jazz, I am never really comfortable with too much out of tempo stuff. One of the things I really liked about jazz and rock music was that kind of physical movement. So, I tended to put that in, or change the time signatures slightly.

Did playing so much live influence the way the second album turned out?

Robert: Yes, I think that is possibly absolutely right.

Splitting up

Do you have any memories from when you decided to split up the band?

Robert: I realised that in Soft Machine, I couldn’t be a follower. And in Matching Mole, I found out that also I couldn’t be a leader. So I was left with these two things. And then it occurred to me! My inspirational light bulb moment was: ”You don’t have to be in a band, Robert! It is not a law.”

For all that time, because rock groups started about the time conscription in the army ended, I always saw it as an extension of going into the army. In the early 60s all young men went into the army to occupy foreign countries for a few years and sit around drinking beer, and picking up local girls and so on. And when they stopped recruiting soldiers, the Beatles went to Germany and did exactly the same thing! Ha ha ha!

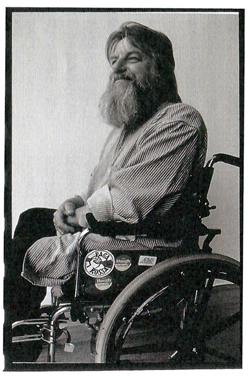

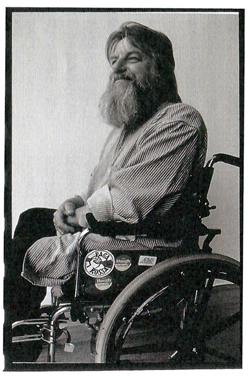

I always thought that you have to be in a sort of gang, but no you don’t. You don’t have to do it! I was liberated in the end by – people think I am being ironic – but, I was liberated by being in a wheelchair. A band was no longer a possibility. It is a paradox, but I am totally happy that it happened now.

But there was talk of a new incarnation of Matching Mole?

Robert: Dave MacRae wanted to form a jazz-rock trio. And I didn’t really want to go that jazz-rock way. I don’t really like what came to be known as jazz-rock. There are some very nice people playing it, but it seems a bit opportunistic. Jazz musicians who are jealous of rock musicians doing so well and thinking: ”Well I can play instruments better than them. Let’s grow our hair, give ourselves a mystical name, get rid of our horn player and get a guitar player and we can play rock better than them.”

So, I didn’t want to be in a jazz-rock band. I was trying to think about a keyboard player, really. And the one I came up with, who was lovely, was a man called Francis Monkman who played with Curved Air. He had no jazz in him, but I worked with him on a radio broadcast that was later put out on American label Cuneiform. He was brilliant, very imaginative also, from a classical background.

But I just didn’t know what to do and I thought: ”Well I want a jazz player, but someone like Gary Windo who just doesn’t play like a session musician. And Bill again maybe.” I was working on that, and I could imagine a few tunes with that, but I couldn’t imagine spending a year just with that. So… I was sort of saved from all of it by just falling out of a window. Into another planet, ha ha! Into another world.

So as a solo artist, you have been a leader of yourself for the rest of your career.

Robert: Yeah, that’s right. I boss myself around. There are no bad feelings that way.

The Italians of the East

I saw on Youtube that you did a kind of a workshop at pub last year, where there was some playback of your music and you were talking in-between.

Robert: Yeah, there have been a couple of those. One for Wire magazine, and then for Cafe Oto in London, they have a music venue over there, run by a Japanese person.

Would you be at all interested in doing something like that in Japan?

Robert: I would have been, but in fact I am not travelling anymore. I don’t go on airplanes anymore. The thing is, my wife is older than me. She is in her 70s and she is not very well. She has been struggling with her health. Having been fairly selfish most of my life and just doing my thing, I am trying now to be more just kind of domestic.

I would love to go to Japan in the sense that they are wonderful. I get lovely letters from Japan, and beautiful gifts, lovely things. Somebody asked me to name their new restaurant, and I did that, it is called ”Happy Mouth”. And I’ve got Japanese neighbours here. But I can’t travel anymore.

Certainly, musicians who play there love it, and I feel sad that I am missing that, but I can’t deal with it any more. I am not interested in talking about my disability, because as you gather, mostly it has been almost an advantage, making me concentrate and simplify my life. But that said, next year will be my 70th year, and I am getting health problems. I just can’t do things I used to be able to do.

I am so grateful to Japan, in some way they are kind of the Italians in the East. Because the two places I get the most alive and lively, understanding and friendly responses: in the West is Italy and in the East it is of course Japan. And those two areas of people listening have been my best encouragement over the years, absolutely no question.

Thank you for talking to me today!

Robert: I am sorry I gave you a bit of a hard time in the beginning… Temperamental musicians, what can you say!!

>> The interview on the Popgruppen website.

|