| |

|

|

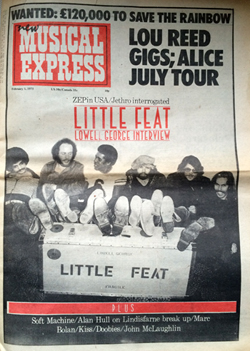

Looking' Back - The Soft Machine Part 2 - New Musical Express - February 1, 1975 Looking' Back - The Soft Machine Part 2 - New Musical Express - February 1, 1975

|

|

IN LAST week's issue, Part One recounted the history of the Softs from their schooldays to the break-up of the group following the recording of their debut album in 1968. This week we take up the story with the reformation of the band in 1969.

FROM FEBRUARY to early April '69 Wyatt, Hopper and Ratledge rehearsed daily at Wyatt's mother's house in Dulwich, South London. April was the month in which they were scheduled to record their second album and the material they were organising was intended primarily for the studio, not the stage - in fact, none of it was performed "live" before the album was finally cut.

This - and the wholly new complexity of their more recent music - contributed to the slight stiltedness of the final takes on "Volume 2", although this drawback is almost totally occluded by the poor quality of the recording itself.

The Softs, still smarting from their New York experience, had resolved to handle the production themselves, a decision which nearly proved fatal. Almost everything that can go wrong in a studio went wrong - and the band possessed little of the experience required to conquer these problems.

Ratledge, for some reason obsessed with avoiding a repeat performance of his astonishing handling of the Lowrey organ on the first album, insisted on laying all his basic tracks down on a concert grand; acoustic piano being one of the hardest instruments to mike up, the band not unnaturally got it wrong - with the result that the piano tracks, already too reverberant, "leaked" onto the tracks adjoining them, causing all kinds of insoluble puzzles in the final stages. Likewise, the horn tracks (by Brian and Hugh Hopper) possessed little resonance and were duly dominated by the keyboards.

But despite all this - and a truly terrible edit in the opening bars of "10.30 Returns To The Bedroom", necessitated by sheer lack of time for Wyatt to rehearse the devilishly difficult vocal part - "Soft Machine Volume Two" remains almost as much of a rock classic as its predecessor.

Side One features the results of Wyatt's months of work on a heritage of fragments taped by Hopper over a period of three or four years - and it's brilliant. The lyric wit and harmonic sophistication outclass anything in its vicinity, and the group's suave handling of Ratledge's first venture into irregular time ("Hibou Anenome And Bear", erroneously attributed to Hopper), is a delight in itself.

On Side Two a pair of quasi conventional songs (Ratledge's high-stepping farewell gesture to the departed Ayers, "As Long As He Lies Perfectly Still", and Hopper's hauntingly enigmatic "Dedicated To You But You Weren't Listening") precede Ratledge's ten-minute session of 7/8 gymnastics, "Esther's Nose-Job" - a composition which would provide an ever expanding flag waver with which to close the group's sets over the next two years.

BUT THERE WAS no time for them to get the results of their labours into any perspective.

Sean Murphy had just taken over in the management department (although Mike Jefferies controlled the royalties situation on the first two LPs, and the group are still involved in prolonged litigation alleging that they never received a penny from either of them). The show was finally on the road and an endless succession of gigs stretched to the end of the year.

The band, using a regular set comprising (in running order) "Moon In June", Hopper's "Facelift", Ratledge's unrecorded "Eamonn Andrews", Hopper"s "Mousetrap" (the latter parts of which - including the beautiful sequence "Backwards" - form the second part of "Slightly All The Time" on "Third"), and "Esther's Nose-Job" (plus "Hibou, Anenome And Bear" as the encore), toured continuously for six months - until Hopper, who had recently taken to playing his bass from an almost supine position in an armchair stage left, declared himself bored and desirous of fresh stimuli.

Wyatt and Ratledge, brooding on possibilities and only too conscious of the imminence of a second break-up, happened to catch The Keith Tippett Group at The Marquee one night in October. Particularly impressed by Tippett's red-hot front-line trio of Elton Dean (alto/saxello). Marc Charig (tpt/flugel-horn), and Nick Evans (tmbn). they enticed the gentlemen into the world of rock with promises of fame, fortune, and centrally-heated groupies.

Dean recommended tenorist Lyn Dobson (who also played sitar, flute, and harmonica) - so that within a couple of days The Soft Machine was a seven piece and off on a singularly gruelling two-month tour of France.

It's one of rock's biggest frustrations that this line-up never recorded together (aside from one rather lacklustre date-on Top-Gear"), because the fact is that, playing adventurous charts scored 50-50 by Ratledge and Hopper, the expanded version of The Soft Machine was not only the best-ever line-up in the band's history, but one of the most amazing "live" rock experiences then going.

By the time (February 1970) that the group had got around to recording "Third", Evans and Charig had been dismissed for reasons of financial necessity (and the' original trio's pessimism over the role of brass instruments in performing complex scores at the increasing velocities dictated by audience enthusiasm - which was justifiably running very high).

Dobson was the next to go, his anarchic vitality incurring the distaste of the refined and cerebral Ratledge, but not before he'd contributed to the collage of "live" takes of "Facelift" that forms Side One of "Third".

Moreover, Ratledge's "Slightly All The Time", elegantly influenced by the spacious ease of contemporary Miles (eg., "Miles In The Sky", "Filles De Kilimanjaro"), hardly represented the uproarious thunder of the seven-piece - and his new extended composition, "Out-Bloody-Rageous", carried the fascination with time-signatures and "loop" figures into forbodingly sterile areas.

Only Wyatt's "Moon In June", recorded almost entirely by himself and in the face of frankly-expressed disapproval on the part of Ratledge and Dean, was a real advance - its final five minutes, based on another of the Softs' trademark, the "drone", being worth the price of the double-album alone.

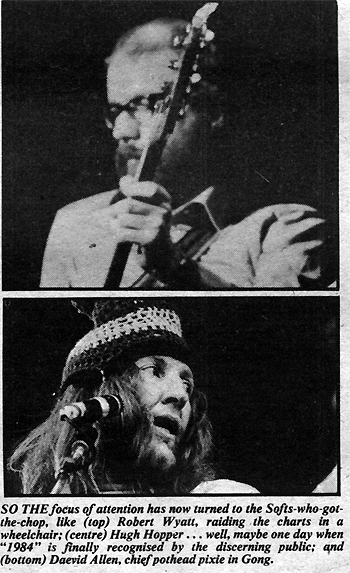

Disturbed by the power-games going on around him, Wyatt subsequently disappeared off to record a solo album and relieve the pressure of his stoppered creativity. This was "The End Of An Ear" and the pun, in retrospect, becomes more serious that it at first appeared.

THERE WAS considerable Cultural Significance embodied in "Third" - "rock coming of age", etc - and the Establishment and jazz critics zeroed in with polysyllabic fervour.

When the BBC invited the band to be the first representatives of rock at the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts, matters (at least as far as Wyatt was concerned) were beginning to get silly.

Increasingly, his popular vocal excursions were being cut back by the demands of more and more fiendishly-technical instrumentals from the pens of Ratledge and Hopper. In addition to this, Dean, was determined to swing things into out-and-out jazz, pushed the music even further from the original conceptions by introducing vehicles for free-form blowing (eg., "Fletcher's Blemish" on "Fourth").

It was only a matter of time before Wyatt would be elbowed out, but an initial trial separation - with him reinforcing the rhythm-section of Ayers' contemporary group The Whole World - didn't work out and he returned to the fold in time to contribute the mysteriously mixed down drum tracks to the totally voiceless "Fourth" (released February 1971).

This was the first of the Softs' albums to appeal to a jazz/rock crossover audience - although many mainstream rockers felt betrayed by sidelong excursions into abstracted vagueness (Hopper's nevertheless extraordinary "Virtually" suite), torrentially melodic solos from the alto of Dean, and Ratledge's most complex (and most successful) composition yet. "Teeth", in which ever-changing time-signatures joust with spikey lines that unravel with a linear steadiness and an ascetic disinclination to repeat themselves.

The music was still healthy enough (although contrasts-available from employing the Wyatt drums and tonsils were almost entirely foregone) and the band's name was further exalted.

In due course they were invited to play the Newport Jazz Festival where Ratledge found himself on the same bill as his idol McCoy Tyner and Wyatt found himself to be having trouble with reality.

Soon after this he decided things had gone far enough and quit to form Matching Mole in September '71.

STUDIO TIME for the recording of "Fifth" was booked for November - which didn't leave much time for the recruitment of Wyatt's replacement.

However, Dean had been playing the odd gig with Nick Evans in a free-jazz unit called Just Us, the drummer of which was the fiery, multi-directional Phil Howard, whom all admired. Well, musically, anyway.

The results of the new combination were explosive, both in musical terms (Side One of "Fifth" is the last really potent statement The Soft Machine ever made) and in personal affairs: Howard and Ratledge clashed egos disastrously and, there and then in the middle of recording, the former was fired.

Nucleus drummer John Marshall was brought in, initially as a session-man, and the group struggled raggedly through Side Two.

In a review in Let It Rock, a would-be contemporary cynic saw the departure of Wyatt and the recruitment of two technically dazzling jazz drummers in succession as proof that the music was getting too complex for a mere rocker to cope with Unfortunately this doesn't pan out from actual listening.

Wyatt was far more adept (because far more self-tutored) at getting around Ratledge's 9/8s and 1 l/4s than either Howard or Marshall; Howard transfigured the metrical exactitudes envisioned by Ratledge into a dizzying blitz of crisscrossing polyrhythms - a firestorm at the centre of which was ye olde 4/4, even if only in terms of pulses felt subliminally - whereas Marshall, schooled in the tepid funk of Nucleus, went a step further and actually played 4/4, gathering the irregular folds, so carefully disarrayed by the composer, into chunky neatness.

Wyatt's leaving coincided with more than merely the rhythmic simplification of the Softs, however. With him he took most of the group's humour and a large slab of their profundity too.

The four or five months following the release of "Fifth" saw the progressive dissolution of the band's inner ties and trusts.

The honeymoon musical partnership of Dean and Ratledge (symbolized by the presence of the latter on the former's solo album, recorded just prior to "Fifth") was over for good. Dean seething at the rejection of Howard. Hopper, in turn, was beginning to feel somewhat out in the cold and when (in May '72) Dean finally quit to be replaced by another ex-Nucleus man. Karl Jenkins, what had at first only seemed like a freeze-out became Antartica a-go-go.

The deal now was technical expertise.

Ratledge had it, Jenkins and Marshall agreed that they had it too; only Hopper, uncomfortably attempting to find a way of playing irregular bass-riffs against Marshall's powerful common-time, had no claim to the diploma the others had awarded each other. Immaculateness was not the sole raison of his etre.

"SOFT MACHINE Six", recorded in the final months of '72, featured a mass of compositions by Jenkins and Ratledge (including many variants of the Nucleus Hip-Riff-and-Funk ideal) and only one Hopper number - the experimental "1983", based on an electronically-embellished and very lengthy musical loop.

Recorded in the wake of the summer '72 sessions for " 1984" (which eventually came out after "Six"), it was intended to be a kind of trailer for Hugh's solo-album. It turned out to be the only vital section of a rather flat and foursquare double-album and, shortly afterwards. Hopper left to pursue his own concerns.

Yet' another jazzer moved in as replacement - bassist Roy Babbington - and the music got smoother and more scintillatingly-played and finally wound up losing its soul somewhere in a glittering galaxy of electric pianos and synthesizers.

"Seven", recorded in late '73, documents the downfall.

Recently, the band recruited guitarist Alan Holdsworth, presumably to win some some popular appeal.

"Eight" is imminent for release - but the focus of attention has long since shifted to the Softs-who-got-the-chop: Daevid Allen and his fanatic ally-subscribed Gong, Kevin Ayers and his urbane gestures towards becoming a teen idol. Robert Wyatt and his multi-faceted musical personality that continues to grow richer and purer simultaneously... maybe Hugh Hopper too one day, when "1984" is finally recognised for the minor master piece it is.

BUT THE Soft Machine, the band Mike Ratledge slowly wrested away from its founders in pursuit of his immaculate vision - well, not even its Gallic followers seem too pleased with it these days.

The key lies in a revealing remark Elton Dean made soon after leaving the group.

"Mike and Hugh's idea of getting it on," he said, "is to play aggressively." Ratledge's own half-serious definition of the Softs as "a brute musical experience" adds further clarification.

For, almost since the Softs re-formed in 1969, Ratledge in particular has appeared to be interested in music as a form of symbolic logic - ie., echoplex pianos playing interlocking phrases = beauty or peace; fast 7/4 and distorted organ = excitement; fuzz-bass roars = drama.

An abstract design for emotive sound.

And, while this objective approach doesn't of consequence preclude expressivity (qv.. Bach, Stravinsky, Bartok for music frequently at its most moving and most impersonal at the same time), Ratledge's viewpoint is ultimately a mechanistic one in which all those frail, wobbly, imperfect, and imprecise human experiences (like intuition, inspiration, doubt, love) finally default to symmetry.

It's doubly significant, thereby, that Wyatt's first move away from the Softs, the "Matching Mole" LP of early '72, is an album primarily about misery. Musically shakey, it devastates anything by the corporate cool smoothie The Soft Machine has become in the last two years sheerly in terms of emotional engagement.

The Softs haven't lost their artistry. Ratledge is as original and unique as ever, if his fellow band-members hardly sparkle in their present combination.

What they have lost is their commitment. The Establishment got 'em just as soon as they agreed to play the Proms.

Softs connoiseurs will remember, I'm sure, that that performance came close to disaster when Ratledge's trusty old Lowrey refused to work at the begining of the set. Eventually a kick persuaded it otherwise.

There's a moral or three in there somewhere.

Part One

|