| |

|

|

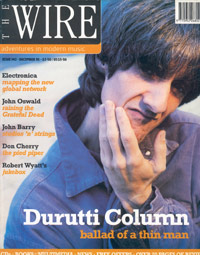

Invisible

jukebox - The Wire N° 142 - December 1995 Invisible

jukebox - The Wire N° 142 - December 1995

INVISIBLE JUKEBOX

|

|

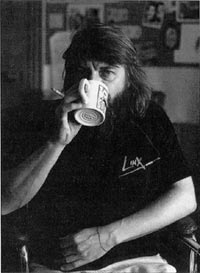

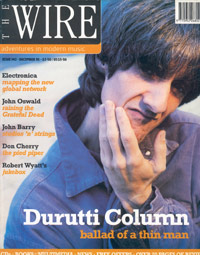

In 1973 Robert Wyatt fell out of a window at a party and

suffered an injury which left him paralysed from the waist

down. Although it effectively ended his spell as one of

the UK's most inventive drummers, his musical career continued

- he happened to be one of the UK's most inventive singers,

songwriters and arrangers, too. Beginning as a drummer and

singer in The Wilde Flowers in mid-60s Canterbury, Wyatt

went on to a famous five year stint with Soft Machine. In

1972 he formed the more spontaneous, and equally acclaimed,

Matching Mole. Post-accident, Wyatt found his true voice

and recorded his best work, starting with Rock Bottom in 1974. The same year, his version of The Monkees' "I'm

A Believer" made the charts - a feat repeated eight

years later with the Elvis Costello song "Shipbuilding".

In between his own releases, his collaborations have been

many and various, from Brian Eno to Mike Mantler, Working

Week to Ultramarine. Wyatt joined the Communist party in

the mid-70s and his work became increasingly political throughout

the 80s. After a five year hiatus, he re-emerged in 1991

with Dondestan, his best work for 15 years. An instrumental

mini-album A Short Break followed. He is currently

negotiating a new record deal. The interview took place

in Wyatt's home in Louth, Lincolnshire.

| |

|

CHARLES MINGUS

"Haitian Fight Song" from The Clown (Atlantic)

|

| |

|

I never saw this band. I do think he's underestimated

in importance as a bass player: it's good that you've

got one here where he starts on his own. I think he's

probably my favourite ever bass player. Apparently

he used more fingers than other bass players. He used

three fingers of his right hand, which is why you

get rather uneven walking lines, using the middle

finger and the first finger. What I like about his

solos is that they're the most like speech patterns

of any bass player, so that makes him the most remarkable.

This has got a strong melody and even though it's

just a quintet, it's like a whole group feeling -

not just soloists and a rhythm section, a real group

[Looks at CD] It's from The Clown! My God, that is

going back.

In your biography you mention a lot of bass players

as major musical influences.

It's what drummers work with - we're both in the engine

room so they're the ones you get to know and that

can be the crucial thing. Also when I'm making a record,

it's the one thing that I can't do myself, so I have

to get in a bass player.

One of the things that influenced me about Mingus

is the compositional thing. There's a tendency in

jazz, and it can be allright, for each composition

to be a vehicle for the soloists to do their stuff

- that's the only reason that tune is chosen. Whereas

with Mingus, each piece has got its own character

and it's very particular. And even with a small group,

an informal set-up like that, they're playing that

piece, not some other piece - that's what I like.

Because he came from the West Coast and not the East

Coast, he got involved in a lot of his early workshops

with a mixture of all sorts of strange people that

he might not mix with in some other context. But the

first groups he had were extremely academic sort of

intellectual exercises, the Mingus Workshops. He gradually

got bluesier, but his bluesiness had a terrific intellectual

authority because he'd done all this technical homework

beforehand. So he was in total mastery of time signatures

and harmonic complexities and so on.

|

| |

|

THE RAINCOATS

"Fairytale In The Supermarket" from The Raincoats

(Rough Trade)

|

| |

|

It's English anyway. Could it be The Slits? Is it

Palm Olive? I really think she's good - let me get

in a plug for Palm Olive as a fellow drummer. I once

said [to The Slits], 'If you ever want me to drum

on your records I'd be happy to come', but they never

asked me. I was very hurt by that, but never mind,

I got to play with The Raincoats instead. It's not

The Slits? Blimey, I'm pleased I recognised the drumming.

It's Palm Olive and somebody Yeah Go! Go!

It's from The Raincoats' first album, with Palm

Olive on drums.

I did the last gig in my life [in 81] with The Raincoats.

We did "Born Again Cretin", which they did very well.

I really enjoyed it... I didn't know [this] was The

Raincoats because I didn't hear their first record.

To be fair, that definitely wasn't Ari Up singing.

What threw me was distinctive drumming style that

I associate with The Slits - that's my excuse. Very

nice. I liked that.

How did you come to play with The Raincoats?

I think they were an Rough Trade and we met around

Rough Trade. It was a fairly loose set-up where people

were listening to each other's stuff and clocking

what each other were doing.

You played with other post-punk groups and musicians

- Scritti Politti, and Epic Soundtracks from Swell

Maps. Few other musicians from your generation got

so directly involved in that area.

Well it surprised me, to be honest. If I was asked

and I could do it, on the whole I would. I liked the

attitude round then. There were a lot of people I

got on with better from that eruption than from that

early period in the 70s, that I might have been expected

to identify with. I liked the rough and ready approach.

It's like somebody said about me: I'm like Jimmy Sommerville

an valium, and I haven't got his get-up-and go, I've

got a lot of get-down-and-stay. But apart from that

I really liked all the people I heard from that period.

I didn't think rock'n'roll was so precious that it

had to be played in tune. It never struck me as the

essential ingredient in the first place. In fact by

having that strange detuning that they all seemed

to do - that slightly untuned desafinato that they

had - it gave a bit of harmonic interest to a music

that normally doesn't have any at all. The music I'd

been involved in listening to before, the jazz, had

gone into a tailspin of rejection of organisation

anyway. So quite a lot of pop groups at that time

were a sort of electrified version of a free jazz

revival - which to those of us who were accustomed

to these things was quite nostalgic really.

|

| |

|

VARIOUS

ARTISTS

"Smash The Social Contract" from Cornelius

Cardew Memorial Concert (Impetus)

|

| |

|

Oh it's Communist Party, brackets, Marxist-Leninist,

close brackets. Could it be Laurie Baker, the composer?

I think I recognise that pianist. Oh, that's very

interesting that, because Cornelius Cardew used to

write a lot of pieces, but I don't think that is Cornelius

Cardew. Although he did take on the attempt to write

popular songs, that would have been in the era when

I don't think he specifically dealt with things like

the Social Contract. The things I remember by him

at the time were more Internationalist, but it may

be.

It is composed by Cardew, a performance from his

memorial concert in 82.

Is it really? Oh, that's interesting. It could have

been Laurie Baker on drums [Looks at sleeve] Laurie

Baker, there you are.

One thing to say about Cornelius Cardew, before anybody

says 'what a load of crap' or anything like that,

is he was the most stunningly knowledgeable musician.

One of the few in this country that had that really

encyclopaedic knowledge of music, that we associate

with non-English figures like Pierre Boulez and people

like that. And had he lived he would have been recognised

as one of the giants of music, just because of the

breadth and depth of his knowledge. What people object

to, of course, is the way that he channelled that

vast knowledge into certain disciplines, but I think

that's very heroic myself, and it was very interesting

to hear it.

Cardew was obviously keen to get his message across

to the greatest number of people by putting it in

an accessible 'popular song' form. But do you think

the rather knockabout knees-up style of this particular

song actually works?

Well the thing is, they set themselves more problems

than they tried to solve, because by seeing what you

could do without really using Transatlantic popular

culture at all, your departure point into the new

age comes from somewhere around Gilbert & Sullivan

in the end. So you end up becoming Marxist-Leninist-Gilbert

& Sullivan-ist! Nobody in England should object

to that - we're all very proud of Gilbert & Sullivan.

I would suspect anyone's political motives of disapproving

of Cornelius Cardew on those grounds. It's the great

thing, innit, Britpop, this year? You can't get more

Britpop than Gilbert & Sullivan. So he was right

in there, Cornelius, ahead of the pack as usual.

I'm not saying he got everything right, but I like

his attitude with all this knowledge, trying to focus

it instead of bathing in it in a sort of narcissistic

glory of talent. He never tried to do that and I think

it's very unusual.

|

| |

|

HATFIELD AND

THE NORTH

"Fitter Stocke Has A Bath" from The Rotters Club

(Virgin)

|

| |

|

Oh,

that's Richard [Sinclair]. What a lovely voice, it's

so true. On Rock Bottom he and Hugh Hopper

really held it together [on bass]. In the mid-60s

- he actually came from a musical background, his

dad was a musician - although he was younger than

us, he always used to sing in tune which I thought

was pretty avant garde at the time, and actually I

learnt to do the same. It took me a few years. A musician

that he liked even when he was a teenager was Nat

King Cole, who nobody listened to in the 60s. Nat

King Cole people don't realise why singers like him

so much. It's because he's so in tune, so accurate.

That's half the battle really - and Richard always

was.

Hatfield And The North were one of the most fêted

groups from that whole Canterbury Scene of the 60s

and 70s. Was there any sense of a 'scene' at the time,

or has it just become labelled thus with hindsight?

The first time I heard of the Canterbury Scene was

in an article. It was invented by that bloke who does

family trees [Pete Frame] and in order to do family

trees, you have to have families. If I hadn't been

told I was in a thing called the Canterbury Scene

it wouldn't have occurred to me. It surprised me that

such a thing came to pass and it was interesting how

these history books eventually get written. It makes

you wonder about them [Laughs]

I had a very, very unhappy and unsuccessful time at

school in Canterbury, during which time I actually

lived nearer Dover. I think in the long run, despite

some very nice and to me now seemingly essential associations

like Hugh Hopper, I was unhappy in Canterbury. I know

Dave Sinclair [Ex-Caravan and Matching Mole] is very

affectionate about it. I never had that kind of ruralist

affection. I was taken to the country at about the

age of ten, simply because my Dad had a terminal illness

and retired early, somewhere where he could take it

easy for a few years. As far as I was concerned, my

life was shut up in my room doing little paintings

and listening to records - so what I really remember

is the records I listened to and the paintings I tried

to do. Highlights were saving up enough money to go

to London to concerts, or buy an Ornette Coleman record.

I wasn't primarily interested in music for a start,

and secondly, I certainly couldn't play. People have

put out demos and tapes from that period from the

60s which I'm on, and I just find them so ridiculous

I can't believe anybody wants to listen to them.

|

| |

|

KING

CRIMSON

"Cat Food" from In The Wake Of Poseidon

(Island)

|

| |

|

I'm

trying to work out where that bassline comes from.

Oh, what is that? People do that, use a classic bassline

and it throws you. You spend the whole time trying

to remember what it is. Oh, John Lennon. It's from

a Beatles... that one they did on the roof. It's very

interesting indeed. They can all really play [Wyatt

later identifies the bassline as coming from The Beatles'

"Come Together".]

It's King Crimson from 1970 with Keith Tippett

on piano.

I was going to say, the pianist was particularly good.

[Laughs] Michael Giles on drums? He's a terrific drummer,

I should have guessed it from that. To be honest a

lot of bands came up around 68, and in 68 we [Soft

Machine] were in America. What I heard of the other

bands at that time were Big Brother & The Holding

Company, Sly & The Family Stone and The Buddy Miles

Express, and Larry Coryell playing in the smaller

clubs. American groups, basically, and of course we

were with Hendrix. I didn't really know much at all

about English bands who would have been considered

our contemporaries. I don't remember ever actually

going to a rock concert that I didn't have to play

at.

One of the reasons that we played this track is

that it's an example of the meeting ground of Progressive

rock with experimental jazz of the era. Both King

Crimson and Soft Machine used Keith Tippett's horn

section [Marc Charig and Nick Evans]. King Crimson

also collaborated with South African exiles like bass

player Harry Miller, while you collaborated with brass

players Mongezi Feza and Gary Windo.

The connection is very simple - Keith Tippett's personality.

A West Country bloke with a great big heart and completely

unlike the Old Boy Network jazz mafia that was the

London scene at the time. He had all barriers down,

listened to everybody, open-minded, never put anybody

down, and one of his things was to get all these different

musicians from different genres together - particularly

the South African exiles. He would get together these

bands and get us into them and then we'd meet each

other. So really you could put a lot of that down

to one man.

I think Mongs [Feza] and the South Africans we knew

anyway, because we used to go down to Ronnie's old

place and see The Blue Notes when they came to London.

Although I didn't know them personally then, it would

certainly have helped getting acquainted with Keith

Tippett and Gary Windo and all those people. Alfie

[Wyatt's wife] knew Johnny Dyani and Chris McGregor,

and when we got together in 70- 71, I also got to

know her friends as well, so that would be another

connection. It was Alfie, Evan Parker pointed out,

who introduced him to John Stevens, for example Chris

McGregor was another one with a big heart.

|

| |

|

NINA

SIMONE

"I Put A Spell On You" from I Put A Spell On You

(Mercury)

|

|

|

[Immediately] Ah yes, this is nice to hear [Sings

along]. There's a fantastic saxophone solo on this

but I don't know who it is. It's so great [Sings along

to solo] Yeah! Then she picks it up and he keeps on

going, he keeps pushing it. Now he's finished.

Cor, that's the stuff. The saxophone solo is like

some of the players who played with James Brown: Maceo

Parker.

Now, there's a thing that pissed me off a few months

ago. Everybody's favourite parliamentary candidate,

Screaming Lord Sutch, was on [the radio] and boasting,

quite rightly, that he's the one who eventually got

rid of David Owen by beating him in an election -

which is a great contribution to British politics.

But then he was on about how he did everything before

everybody, long hair and all that, and then he talked

about all his coffin stuff and he was way ahead there;

but he got all that coffin stuff and that whole act

from the bloke who wrote this song, Screaming Jay

Hawkins. For him [Hawkins] the "spell on you"

was the big thing. He was into all that necromancy

and I don't know what else.

Didn't you used to sing this with The Wilde Flowers

in the mid-60s?

I think I used to sing it but I have a hard time remembering

more than about 20 years ago to be honest. But certainly

Nina Simone was very important. In fact most of the

singers that I was influenced by were women, funnily

enough. I seem to have more affinity with women's

voices than with men's. That's because my voice never

broke really.

I think she's a great singer, not just a good one

I'd put her up with Ray Charles. The thing is, she

doesn't quite belong anywhere. Really she belongs

in the continental tradition of chanson singers, Jacques

Brel and all that sort of thing, Edith Piaf - that

dramatic presentation of songs. It partly came out

of a folk tradition of music hall but not the jokey

side of it. Oscar Brown Junior was that as well. It's

not pop and it's not jazz, it's not any of the categories

that now exist. It's more intimate, more nightclubby.

Amazing presence. When she's in Ronnie [Scott]'s she

makes the place look really small. It's like having

a real queen in a room, the real nature's aristocracy.

By the time I saw her, she was no longer hitting the

notes. She just sort of intimated them, sketched them

in the air. And it was all you needed if you knew

the songs.

|

| |

|

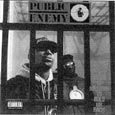

PUBLIC

ENEMY

"Party For Your Right To Fight" from It

Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back (Def

Jam)

|

|

|

|

Sounds

like they're sampling Sly Stone NWA or something like

that?

It's someone equally well known.

Not by me, evidently. It's not Public Enemy? I'm trying

to work out what they're sampling. Oh well, I know

this one. I think that's one of the great lines "It

takes a nation of millions to hold us back".

It completely inverts the whole notion of dissidence.

It's very close on from The Last Poets, the first

people who did this kind of thing, without a rhythm

section, just a cappella.

What I like about [rap's] kind of talking - in posh

music it's called Sprechgesange - is that for

some reason it liberated words. There's been a problem,

I think, in black pop music since Motown. Even in

some of the stuff I really love, the lyrics are a

bit like rhyming soap operas. What's nice about all

this black Sprechgesange is that it actually

liberated the language that you could use on a pop

record. It was a shame because in all this time, the

black Americans were reinventing the English language

every five years and made a massive contribution throughout

the century, probably even before, to revitalising

the language, then you get the Motown pop songs that

sound great but they all just go "Ooh Baby".

It was a waste of all that fantastic vocabulary that's

been cooking in the streets - so it was very nice

that it broke through [with rap].

Although Public Enemy get their message over without

any compromise, there's some witty interplay going

on between Chuck D and Flavor Flav.

I used to listen a lot to Peter Tong's rap sessions

on Radio 1 and there is some very funny, very witty

stuff going on. And as for the stuff that people think

is terminally defensive in attitude, I don't think

that anyone who hasn't been to America and been around

on the streets... I don't feel you can talk about

it unless you've been there. It's a long time since

I've been, 25 years, but I found white American racism

made me feel ill and I wasn't even particularly interested

in the subject at the time. But if I lived there,

I think I wouldn't really be answerable for what it

would do to my brain - and that's just me. So what

it must be for someone who's in the firing line, I

can't imagine.

|

| |

|

SLY

& THE FAMILY STONE

"Don't Call Me Nigger, Whitey" from Stand!

(CBS)

|

| |

|

[Immediately]

Oh, that is Sly Stone [Drums on table] Yeah, there's

one thing about Sly Stone that I really like. First

of all it's like Mingus, there are lots of dimensions

in it - a foreground, a middle ground and a background,

and there's something happening in all of them. It's

very beautifully spaced. Also that Mingus thing of

each piece is a whole world of its own. [During wah-wah

harmonica break] Another thing is, I was very influenced

by him in this business of the wordless'vocal guitar

solos' [Wyatt's trademark scat style].

Funnily enough, I was listening to this track this

morning and it suddenly became apparent that it's

like your own vocal style.

That's it. Almost like harmonica solos with your mouth

right up to the mic [cups hand over mouth to give

wah-wah effect] and you take a breath. Wonderful.

And I thought, 'Yeah, I can play solos now!'

I went to see Sly Stone when I was in the States,

but the record that most knocked us out when we [Soft

Machine] were in the States was Stand!. That

was as good as rock music got at the time - absolutely

amazing. And the singers he gets in - that woman's

a fantastic singer. He got ever such good players.

I read somewhere that you're a big fan of [Sly's

bassist] Larry Graham.

Yeah, absolutely. One of the great bass players of

all time and a great singer, deep voice, when he had

his own band after he left Sly Stone. Very weird,

strange person - they all were, but fantastic musicians.

There's so much going on, you can't quite tell...

Nowadays you can get effects with vocoders and stuff,

you can sing through synthesizers and get instrumental

effects and so on, but this is before them and better

than all that really. It could be a vocoder thing

[Sly] had been a disc jockey and knew a lot about

studio technology. It's very good, led onto Bootsy

and all that sort of stuff.

On some of the singles - specifically "Dance

To The Music" - the bass is massively loud.

They had very eccentric mixes. They'd make aesthetic

decisions on each track; where to put things, who

to have doing what, things coming in and out of each

tune. They're great art, Sly Stone's records. And

having been a jazz fan, it's nice hearing rhythm sections

as good as the first one you played. If you're brought

up on rhythm sections like Mingus and Dannie Richmond

then rock can seem a bit pedestrian by comparison.

A rhythm section like that has got the dimensions

of the ins and outs that make it more interesting,

more organic.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

PINK

FLOYD

"Apples And Oranges" from Masters Of

Rock (EMI)

|

| |

|

Is

it Barrett? Is it Jerry Shirley on drums?

It's Pink Floyd, one of the last things Barrett

did with them.

I thought it was the second [Barrett] solo LP. That

bassline's just a major scale going downwards. It

is one of the great tunes, the major scale! [At line

"thought you might like to know"]

See, that's another Beatles influence, it's exactly

Sergeant Pepper - or it's just as likely to

be other way round. Paul McCartney used to listen

to them [Pink Floyd].

That's lovely, it's really good. As you can gather,

sometimes with English musicians, I know the people

without necessarily knowing the music. I didn't collect

records or go to the concerts. I was never a consumer.

I really like them and there again liked them individually

as people. I'm biased because they were very kind

to us and to me. In the early days, they got us out

of some horrendous tight spots when our equipment

blew up, and they would lend us some - and groups

don't do things like that. And then to me, they were

very generous when I had my accident [Pink Floyd organised

and headlined a benefit concert for Wyatt in the same

year].

Musically, it's very refreshing to hear that. I'm

ashamed to say I didn't know it, but I'm ashamed to

say I didn't know

The Raincoats, but there you are. But I don't actually

have rock records to listen to particularly. I see

rock music as a boy-next-door activity. Rock doesn't

have any romantic associations for me. It's what people

like us used to do [laughs], the kind of things we

got up to. That's all I feel about it, but having

said that, I thought it was very inventive. I enjoyed

it very much.

The Canterbury Scene we mentioned before has acquired

a sort of mythic status over time, but not as much

as the 67 UFO Club scene. Was it really as exciting

as it's been made out to be?

Well, you have to forgive people involved if they're

subjective. The subjective facts are I couldn't play

in the 60s. It took me a long time. So I associate

the entire decade - if there is such a thing as a

decade - with excruciating embarrassment on my own

part. And it's bound to colour what you think about

a place or a time.

Objectively, I'd say it was good, yeah. It was good

in the sense that the groups weren't the only thing,

just part of what was going on.

It was almost like having a big indoor market, really.

We [Soft Machine] used to go down there and play,

and sometimes they'd have Monteverdi playing, and

the atmosphere would already be perfect. All you'd

need was Monteverdi playing and people wandering about,

or lying on the floor and things like that, and Mark

Boyle's and various other people's film projections

all over the walls, and already that was it, the atmosphere.

And then there would be the groups. It didn't rely

on the groups, it was a place to be anyway. As a stage,

the audience were all in the play. And except for

a few stars in the old style like Arthur Brown, who

was wonderful, most people were fairly anonymous.

They would just be there as part of making the scene.

I think at that time, I was still too much of a jazz

and blues fan to quite be able to tune into what they

[Pink Floyd] were doing. The bands I knew in London

before them were Zoot Money and Georgie Fame. I was

more used to the Ornette Colemans and the Sun Ras,

and compared with what was going on [in jazz] by the

mid-60s, even the most non-poppy pop groups seemed

fairly tame to me, and fairly commercial.

That's not a criticism, it's just a fact.

|

| |

|

TONY

WILLIAMS WITH MILES DAVIS

"Agitation" from ESP (Columbia)

|

| |

|

[During

Williams's long drum solo introduction] Sounds like

Elvin Jones. It's not? Good Lord! He was very influenced

by Elvin Jones - School of Elvin Jones. [Trumpet comes

in] Well. Oh, in that case it's Jack DeJohnette.

It's not actually.

Hang on. OK. It's Tony Williams. Stupid, I am! Oh

God, shoot that man. What a funny mistake to make.

But that's a really interesting mistake, because I'd

never thought of Tony Williams as being anything like

Elvin Jones. But that early section and the business

of stumbling over where you expect the bar-line to

be, is such an Elvin Jones-y thing. And it's a much

deeper sound than I associate with Tony Williams:

he usually has a much lighter, crisper sound.

It was a very important time for Miles Davis. He never

really recovered from the loss of Coltrane and he

nearly went under then, I get the impression. But

it was finding Tony Williams and doing a whole new

thing that put him back on track. I don't know this

one, I have to say. This is terrific, I really like

this.

It's from ESP from 1965.

I should have this, let alone know it. Miles Davis

started recording when I was born and he's been there

all my life. And if someone asked me what was my very

favourite voice sound ever, I'd have to say Miles

Davis. There's a jazz writer, lives in Paris, called

Mike Zwerin, who I've been in touch with again recently.

He reminded me that one of [Miles's] bon mots - he

lives in France so he can say things like that - was

'play half'. And that's exactly right. It's got a

Zen appeal to it. The first time you hear it you think,

'Oh, that's easy, I've only got to play half', and

then you think, 'Which half?' [Laughs] Miles Davis

is one of the great jazz philosophers. It pisses me

off when people list great philosophers and only list

great philosophical writers, because to me some of

the great philosophers weren't writers, they were

people who did other things. Thelonious Monk or Miles

Davis.

|

| |

|

BRIAN

ENO

"My Squelchy Life" from Nerve Net

(Opal/Warner Bros)

|

| |

|

I

was going to play you another piece [ie Eno's "My

Squelchy Life"] but it seems I've recorded over

the tape by mistake.

You'll have to hum it! [After about 20 seconds of

me humming] Ah, hang on, that could be Johnny Rotten.

Don't tell me, because I know who that is. That's

stupid - I just remember him saying something about

sex once that that reminds me of. Of course it's Brian.

I think Brian would be very amused, first of all that

you sang "My Squelchy Life" and I said 'Johnny

Rotten'. And secondly, I would think this is only

acceptable if you point out that we've broken new

ground here, in that you've not actually played the

record and I commented on it. I think it's appropriate,

Brian would really appreciate that.

I have no objective opinion of Brian at all. I just

consider him a great friend and an utterly good bloke.

What else can I say? Brian and I used to spend a lot

of time together in the 70s just talking and hanging

about. Which, despite this thing about various scenes

I may have been on, I don't remember doing with musicians

on the whole. We used to have such fun. That's why

it's so appropriate you didn't play the record, because

we used to have fun imagining things that there could

be. One of the things was in the 70s there wasn't

the word World Music. We thought wouldn't it be great

to get all these records that we were listening to

from all around the world, totally nothing to do with

pop or rock 'n' roll or jazz or American music, anything

like that, anything to do with Europe at all, and

you could find tracks that would appeal to people

and just package it like pop music. It's difficult

to explain now that kind of idea has become commonplace,

in fact hackneyed, how exciting it was at that time

to draw up these sort of thoughts. He was a very enjoyable

person to think with. I find that thinking out loud

with Brian is incredibly good exercise for the brain.

You performed on Music For Airports in the late

70s, which is now regarded as a landmark in Ambient

music. The idea that it was equally valid to listen

to or ignore the music seemed very radical at the

time.

That's perhaps why we got on well, because I do like

that thing that he does and we both do, which is,

'What if you turn the situation upside down, whatever

the assumption or premise might be?' You're banging

your head on the wall to try and do something to grab

people's attention - what if you do the opposite?

[Laughs] Ideas circulate and I'm very loath to attribute

ideas solely to one person or anything. This question

of authorship wouldn't really be a battleground [for

Eno]. Although he is a fountain of ideas, he wouldn't

promote himself necessarily as such, because he's

interested in the circulation of them, and they go

through various processes.

I remember a thing that I'd mentioned that I'd came

across from Miles Davis. He [Miles] was talking about

how to arrange things in a piece of music. And Miles

Davis basically wouldn't tell anybody what to do -

his arrangement was the choice of musicians you had

in the first place. And Brian thought that was terrific

and went on to do some things like that, where you

wouldn't tell anybody what to do - the arrangement

was choosing the musicians. And so that idea you can't

attribute either to him, or to me, I think you'd have

to attribute it to Miles Davis, but the point is,

the idea was very illuminating.

Eno always used to describe himself as a 'non-musician'.

I don't know what it means in rock 'n' roll, frankly.

[Laughs] As opposed to who? Dave Clarke? What are

we talking about here? But that's good. It's the great

saving thing about pop music. There's a lot of pop

music you only have to be able to hear in your head

to be able to do it. But that only makes it like conversation.

There's nothing wrong with that - doesn't mean it's

crap. |

|