| |

|

|

The Rhythm Interview Robert Wyatt - Rhythm - December

2007

The Rhythm Interview Robert Wyatt - Rhythm - December

2007

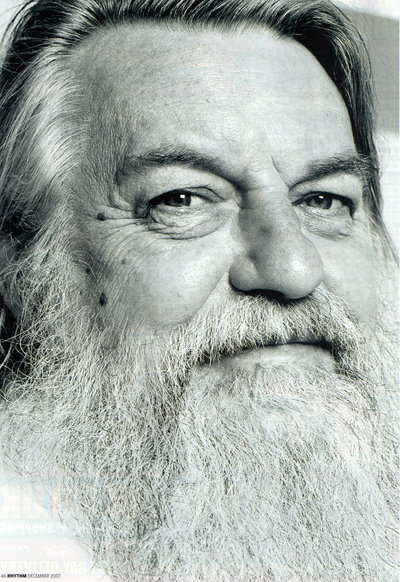

T here's a clear line in the sand when it comes to the career of Robert Wyatt. Specifically, it was drawn in the small hours of June 1,1973, as a West London party thrown by the luminaries of the psychedelic scene brought the first phase of the drummer's life to a disastrous close. A heavy drinker since the '60s due to his pathological fear of crowds, the 28-year-old Wyatt had spent the night consuming punch and whisky in sufficient quantifies that when he fell out of a third-floor window onto the pavement below, he didn't immediately feel any sensation other than "a slight awkwardness at being unable to stand up".

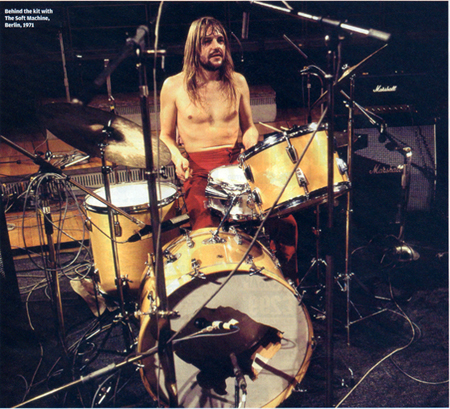

Six weeks later, Wyatt regained consciousness in hospital to learn that he had broken his back, would be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life and, by implication, would never drum again. This last bombshell hit hardest. As sticksman and singer in '60s psychedelic trailblazers The Soft Machine, Wyatt's inspired fills and improvised free-form solos had marked him out as a unique talent amongst the beat generation. After an acrimonious sacking in 1971, he had rebounded with new band Matching Mole, and at the time of his accident was writing material for their third album. Now, after one moment of madness, it seemed he was doomed to dine out on past glories.

The medical report rang true: now 62, Wyatt remains in a wheelchair and has not performed behind a full drum kit for three decades. And yet, rather than bow to his physical limitations, the veteran musician has spent his prolific solo career adapting to them, developing percussion techniques that are arguably as adventurous as his early beats, and draping his compositions with his haunting multi-octave vocal delivery. And now, he is basking in the recent release of his new album Comicopera.

Starting at the beginning, the story goes you were taught by an American jazz drummer...

"His name was George Neidorf and he was staying at my parents' house near Dover in the '50s. He had a real drum kit, which was a novelty. Before that, my kit consisted of an ammunition box, which was my snare, my mother's typewriter as my hi-hat - you'd stamp on it and the keys would clatter back - and an old metal clothes hanger that functioned as a rhythm cymbal. I seem to remember hitting it with cutlery.

"Anyway, George had been taught by Joe Morello, but what he tried to impress upon me was how wonderful Philly Joe Jones was. Then I had another teacher called Ramon Farran when I moved to Majorca in the '60s. He was an old-school jazzer; strict about holding the sticks correctly and elbows being the right distance from the ribcage. It's good to know the rules, even if you ignore them later on."

Who did you take inspiration from?

"People think the white drummers of the '60s were listening to each other, but we were actually listening to black music. The other beat drummers were just boys nextdoor to us; the thing was to get the sound you heard on Stax records. The New Orleans drummers were the bedrock for all of us. Even drummers in bands that don't sound like they play black music learnt how to handle the kit from those bands."

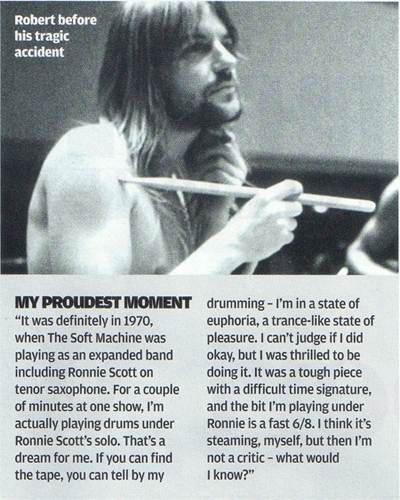

You formed The Soft Machine in 1966 - what were you trying to do with the drums?

"I wasn't trying to be revolutionary - I was trying to get people to dance. Before then, I'd been in a band called The Wilde Flowers, and when we played the local dances in Canterbury, you'd drum in a way that made people dance. When the floor started heaving, you knew you were doing your job.

"I can't think of anyone who was doing what I was, but that's partly because of the nature of the band. The Soft Machine wasn't a proper rock band, apart from the fact we played very loud and had long hair. You needed to be able to deal with any time signature, and you also needed endurance, because once we started pushing the solos, each piece could last over 20 minutes."

Were those improvised solos ever performed sober?

"I can't remember ever being sober once we got going, but that was because l've always had incredible stage fright. I developed my love of music in a solitary state and, to tough it out live, I'd drink recklessly."

What was your approach in the studio?

"Each piece we played in The Soft Machine had its own distinct character - I mean, Kevin Ayers wrote songs that were like Donovan or Ray Davies - so I tried to do appropriate drumming for each. The only thing I couldn't bear was to do the same beat over and over again, so I was a rubbish metronome. I was always having fun on the kit. I'd trick people; go silent when you expected it to go bang and vice-versa."

|

|

Is it fair to say you invented the notion of the singing drummer?

"I honestly don't know. As to how it interacted with the drums, it depended on the music. In The Wilde Flowers, we'd work out songs where I could do them together, or you'd just lay down very regular chops and go onto automatic on the kit and concentrate mainly on the vocals - and sometimes completely fuck it up."

You've said you didn't consider yourself part of the 'Canterbury scene' of the '60s...

"That term was invented by someone who liked drawing up imaginary family trees. I make the analogy with astronomers who look at a random set of stars and say it's a horse or a plough. It's inevitable that you start playing with people around you, but I didn't feel any particular musical connection with them. I felt much closer to the people I ended up working with later on."

Such as?

"A wonderful drummer, who I watched every night on tour in 1968 and still think is woefully under-praised, is Mitch Mitchell. Bloody wonderful. Because Jimi Hendrix was so riveting, people didn't realise just how important Mitch was. He knew his jazz and, like me, he was trying to apply it to the new circumstances.

"At the end of our tour together, I still had a little Premier kit and Mitch knew I couldn't afford a better one, so he gave me his own custom-built maple kit. So from the second Soft Machine album onwards, I was using the same kit as on Hendrix's late recordings. I've still got the cardboard boxes with 'JH Experience' printed on them, which I could probably sell on eBay, but I need them to keep the drums in."

When you were fired from The Soft Machine in 1971, at the time you said it was "humiliating"...

"An experimental band like that is bound to

have a lifespan, but yeah, the end was humiliating, because I'd got them together and they democratically got rid of me. But I was asking for it. There's live footage of those last nights, and there's a real tension, I'm just playing faster and faster, and people are looking at me out of the corner of their eyes. It was untenable."

How did your drumming evolve in Matching Mole?

"That was nice, because it took me back to the happier days of The Soft Machine, so when one of us went dancing off in the opposite direction the others would just laugh and join in. It was more of a fun band, not so solemn. We'd trip each other up, but because we were friends we didn't get the stern glances."

|

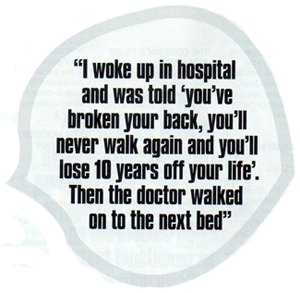

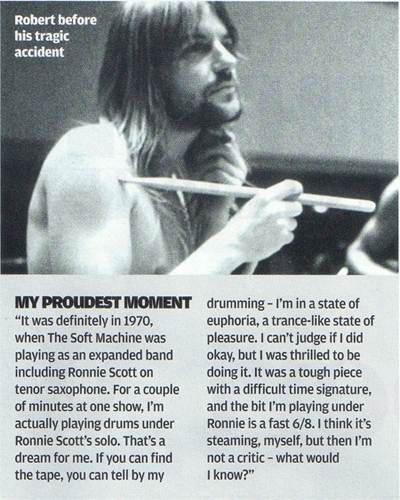

Can you talk us through your accident in 1973?

"That night I'd been drinking punch, then someone got out a bottle of whisky and I was just gone. I was flying - quite literally, in the end, out of the window. I didn't lose consciousness when I hit the ground, but I don't remember anything about the six weeks after that, because they pump you so full of drugs. Then you wake up in hospital and they tell you what's happening, which in my case was 'you've broken your back, you'll never walk again and you'll lose 10 years off your life'. Then the doctor walked on to the next bed."

Was losing your ability to drum the least of your worries?

"Actually, I did think about that pretty early on. I'd been working on a third Matching Mole album, and I thought 'fucking hell - I won't be able to play drums'. Later, I realised I could still sing, then I decided I could still work the top of the kit, and if I needed a bass drum I could prop it up and play it by hand, and I could just replicate the hi-hat by singing it into the microphone. So that made me realise I could record, even if I couldn't play live."

What's your approach to percussion on Comicopera?

"I can still play each bit of the kit separately, so I'll do the cymbal part,

the ride part and so on, and then percussion separately. I often revert to how

I played when I didn't have a proper kit, and I often don't use a kit at all. On 'A

Beautiful War', the off-beat is provided by a Lebanese biscuit tin. Then there's an instrumental called 'On The Town Square', where I used a bodhran [an Irish drum], but with brushes, because I hadn't heard that before. Again, on 'A Beautiful War' the bass drum is me whacking the side of the mattress I was sleeping on in the studio. So I played mattress and biscuit tin on that track - just with a couple of cymbals over the top."

|

|

Don't you ever miss flailing at the kit, as you were renowned for doing with The Soft Machine?

"Having seen clips of my old drumming days, going back 40 years in some cases, I do remember the buzz. But I'm now in my 60s, and I think anyone of that age has twinges remembering their youth. I expect old cricketers remember their bowling when they were in their 20s and think 'fuck, I wish I could still do that'. But you have different stages in your life, and I really enjoy working the way I do now with percussion, instead of being an upfront drummer. Where there's a will there's a way."

www.strongcomet.com/wyatt www.myspace.com/robertwyatt

Comicopera is out now on Domino Records

|