| |

|

|

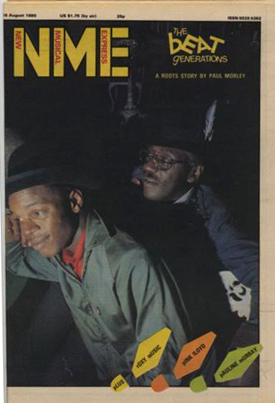

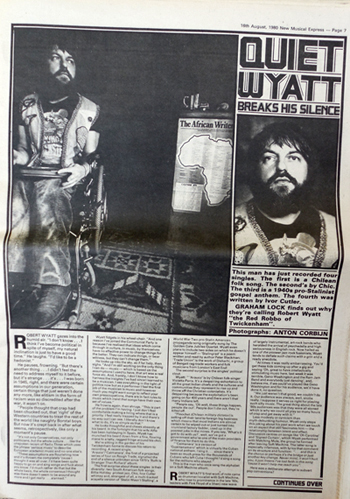

Quiet Wyatt - breaks his silence - New Musical Express - 16th August,

1980 Quiet Wyatt - breaks his silence - New Musical Express - 16th August,

1980

|

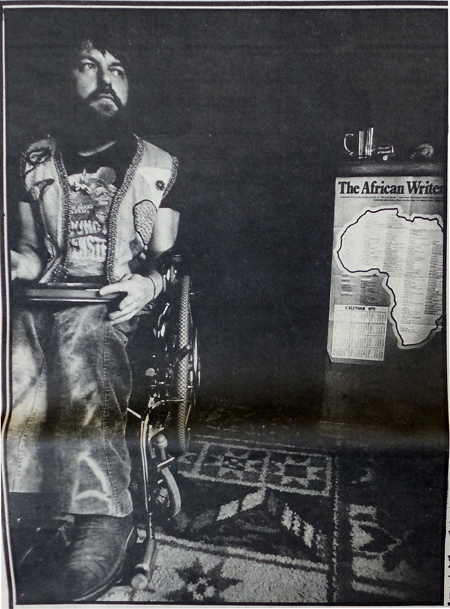

This man has just recorded four singles.

The first is a Chilean folk song. |

The second's by Chic.

The third is a 1940s pro-Stalinist gospel anthem.

The fourth was written by Ivor Cutler.

GRAHAM LOCK finds out why they're calling Robert Wyatt "the Red Robbo of Twickenham"

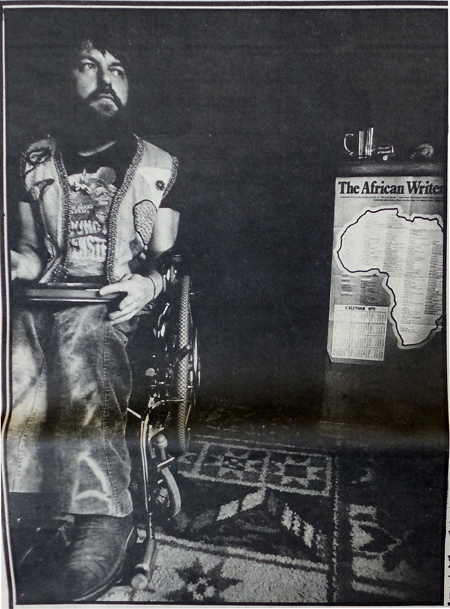

Photographs: ANTON CORBIJN

ROBERT WYATT gazes into the humid air. "I don't know... I think I've become political in spite of myself, my natural inclination is just to have a good time." He laughs. "I'd like to be a hedonist."

He pauses, frowning. "But there's another thing... I didn't feel the need to address myself to it before, but it's strange... it's... I was born in 1945, right, and there were certain assumptions in our generation, certain things that just weren't done any more, like elitism in the form of racism was so discredited after the war, it wasn't on.

"People thought that crap had been chucked out, that 'right' of the Western countries to treat the rest of the world like naughty Borstal boys. But now it's crept back in after what seems, retrospectively, like only a moment's pause.

"It's not only Conservatives, not only politicians, but the whole culture... like the unspoken racism of Radio Three which uses the phrase 'serious music' to describe European academic music and no-one else's.

"These assumptions are flourishing now and it's thrown me completely' cause I thought it was all over. I'd have been quite happy to go on and sing songs and fuck about you know. I'd much rather do that but the whole basis, the whole consensus I thought was there doesn't seem to be around any more and I got really... alarmed."

Wyatt fidgets in his wheel-chair. "And one reason I've joined the Communist Party is because I've realised that ideas which come through in culture, in music, by themselves have no effective power to change things for the better. They can indicate things, or bear witness, but they can't change them."

He looks up into the sky, as if for help, then sighs. "And I'm still working on the only thing I can do — music — which is based on the assumptions I used to have, that art was a real force etc. And, frankly, I don't know how to harness the insights I've had since I learned to be a musician. I see everything in the light of politics now but as a performer I feel the first job of the musician is music and however much you might want songs to reflect your own preoccupations, there are in fact rules to music which insist that songs have their own set of values."

He frowns again, then shrugs. "This is part of the problem I'm having. I just don't feel comfortable making a living where that is a priority. I feel really trapped by it and there's no way out I can see. I literally don't know what to do, it's as simple as that."

He looks thoughtful and chews absently at his beard. In the fortnight that his wife Alfie has been holidaying in Spain, Wyatt has munched his beard down from a fine, flowing mane to a tatty, ragged fringe around his chin.

We're sitting in the garden of his Twickenham home to discuss his return to recording. A recent single, 'Arauco'/'Caimanera', the first of a projected series of four on Rough Trade, signalled the end of a silence unbroken since 1975's 'Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard'album.

The first surprise about these singles is their diversity : two South American folk-songs, Billie Holiday protest jazz. Chic, Ivor Cutler whimsy and, strangest of all, a multi-tracked acapella version of 'Stalin Wasn't Stalling', a World War Two pro-Stalin American propaganda song originally sung by The Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet. Wyatt even plans to include two sides on which he doesn't appear himself — 'Stalingrad' is a poem written and read by author Peter Blackman; 'Trade Union' is the work of Disharhi, a group of Bengali rag-trade workers and folk musicians from London's East End.

|

The second surprise is the singles' political clout.

Wyatt:

" 'Arauco' is by Chilean folk-singer Violetta Parra. It's a despairing exhortation to all the great Indien chiefs and the cultures and communities they represent to rise up and throw off the Christian colonialists. It's despairing because the exploitation's been going on for 400 years and there aren't that many Indians left.

"People say, 'Oh well, these things happen, people die out'. People don't die out, they're killed off.

"Pinochet (Chilean military dictator) is selling off their land to foreign big business which means that most Indians are almost certain to be wiped out or just turned into slumland factory fodder, used up in the poorest jobs in the mines. If you say, 'What's it got to do with us?', well, we've got a government who're one of the main providers of finance for them to do this.

"'Caimanera' is a version of 'Guantanamero' which is virtually the Cuban national anthem. I sing it... since there's been so much press for the thousands of Cubans who left Cuba I thought I'd sing a song for the millions who stayed."

This is the man who once sang the alphabet on a Soft Machine album.

ROBERT WYATT'S first work of note came as drummer/vocalist with Soft Machine, who rose to prominence in the late '60s, leaders with Pink Floyd of a (then) new wave of largely instrumental, art-rock bands who heralded the arrival of psychedelia and high seriousness in English rock. Now hailed as one of the pioneer jazz-rock fusionists, Wyatt tends to deflate such claims with a grin and a ready anecdote.

"At times it was really embarrassing. You'd get these kids coming up after a gig and saying 'Oh, great to have intellectually stimulating music here, last week it was terrible, Geno Washington and the Ram Jam Band and everybody just dancing', and, believe me, if we could've played like Geno Washington and for his audience, we'd have done it, no question.

"We just weren't that good, we couldn't do it. Our audience was always, well, snobs really. I suppose it serves us right for playing such silly music. The great thing about the late '60s audiences was that they were all stoned which is why we could all play so many hours of crap and get away with it."

Less modesty or cynicism than myth-debunking humour, Wyatt only stops this joking about his past work when we touch on an aspect that still fascinates him — the relationship between intent and effect.

Discussion centres on songs like 'Oh Caroline' and 'Signed Curtain', which Wyatt performed with Matching Mole, the group he formed after leaving Soft Machine. The latter song is especially infamous, with lyrics that comment on its structure and function: "... and this is the chorus or perhaps it's the bridge or just another key change. Never mind, it won't hurt you, it just means I've lost faith in this song 'cause it won't help me reach you".

Here was a deliberate attempt to subvert pop conventions?

"Yes, I think so." Wyatt sounds extremely dubious. "I wouldn't call it iconoclasm, I'm not like Magma, trying to change the world by reinventing the language but... I think I was being sarcastic about how seriously people take songs and I was also very exasperated ...

I was also trying at the time to write a real love song and I thought 'What actually is it you're doing? Other people are gonna know how you feel but it doesn't do anything. So what you're doing is something else — just singing a song. And you're trapped in it. You can't actually sing about something else, a song in the end is gonna be about singing — whatever it seems to be about'.

"I felt trapped and so... I think I was just trying to be clever."

Wyatt laughs. But just as he can't help throwing in his self-depracating jokes for fear of seeming heavy, he also can't resist following his ideas through.

"You see, even if you're trying to comrnunicate something, the effect is that what you're left with is an art object which will be admired for its own sake rather than as having pointed something out. An object that entertains people. And if it's not a nice song, if people don't like listening to it, it won't even function like that."

And this, claims Wyatt, holds true despite the artist's intention, despite any formal innovations.

"The artist doesn't have that power... he'll be used by the community any way the community wants to use him because meanings aren't inherent in any object, they're invested in it by observers. Political content can appear and evaporate in the most unlikely places." That mischievous smile reappears. "I mean, I wonder how Blake would feel if he knew that 'Jerusalem' had become the national song of the Women's Institute?"

WYATT REMAINS consistent to his theories of the artist's social impotence, claiming that his new singles were chosen primarily because they were "great tunes". Nevertheless, their content — a heady mix of political statement and oblique personal reflection — corresponds uncannily to the possibilities and confusions with which he is currently struggling.

His next release will be 'Strange Fruit'/'At Last I Am Free'. 'Strange Fruit', originally sun by Billie Holiday in the '40s, was a response to a group of lynchings in the South. Noticing the mass of anti-racist stickers, posters and leaflets that adorn the walls of chez Wyatt, I ask to what extent his choice of that song was affected by this preoccupation with anti-racism.

"It does strike me that people talk as if things are past, Americans particularly, lynchings in the South, killing off Indians etc. But if we talk about the forces that are responsible, they're still at work, they're still largely the same people.

"If you take South Africa, I think — were it not for the growing resistance of the Africans — then the USA, England, Western Europe would be quite happy to turn it into another dust-bowl. We know the USA is actively helping the anti-SWAPO forces, as are the English and the French. That kind of racism is at least as bad as it was in the days of Southern lynchings."

'Strange Fruit' best exemplifies Wyatt's contention that the singles are "like sketches, very undecorated, just documenting a few songs I like". All are mostly solo work, the sound bare and slightly raggedy — here, bass, keyboards and Wyatt's high, plaintive vocals rise and fall with sombre deliberation.

"At Last I Am Free', the Chic song, Wyatt chose because it was "a lovely ballad"."

Although it has no obvious political or personal references, certain lines in the song seem to strike a poignant note in the context of Wyatt's current problems with music. It's just speculation but you could read it as his farewell song to his illusions about rock'n'roll:

"At last I'am free, I can hardly see in front of me."

AFTER Matching Mole had made two albums, Robert Wyatt got drunk at a party one night in 1973, walked out of a fourth-floor window, fell to the pavement and smashed his spine. He's now paralysed from the waist down and is confined to a wheelchair for life.

For a while after the fall, Wyatt maintained his involvement with music. Though unable to use a full drum-kit, he could still handle a wide range of percussion, play keyboards, sing. His comeback album — a second solo (the first, 'The End Of An Ear' from Soft Machine days, has just been reissued by CBS) with the bravely punning title of 'Rock Bottom' — remains the '70s most moving and most neglected masterpiece. A work of real depth, its theme of fall and recovery has an emotional and musical cohesion equalled only by 'Astral Weeks'.

Many people saw the album as being directly about the accident but Wyatt denies it.

"Actually I'd written most of it before the accident. I think the coherence it has is musical, there were a consistent set of ideas I was dealing with through the whole 40 minutes.

After a second album, 'Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard', and two intriguing covers of 'I'm A Believer' and 'Yesterday Man' Wyatt stopped recording. Why?

"My other interests came to the fore. I think what happened was that I couldn't lead the life of a musician — things like travelling just proved too difficult — and it's very hard to be one if you can't lead that life, 'cause it's not something you are, it's part of a set-up — gear, roadies, managers, tours, repertoires. Without all that, I found it harder and harder to keep up a momentum. And the romantic notion of the importance of it all faded quite rapidly. The things I was starting to think were important weren't related to my job. I mean, the people I talk to now, what I do for my fun... like, I go to see films about what's going on in the world and rock 'n' roll seems so... tiny."

Paradoxically, since being stuck in a wheelchair Wyatt's awareness of the world has expanded dramatically. He's now a voracious reader and regularly tunes in to radio stations from all over the globe. It's no wonder then that he's experienced this gradual disenchantment with rock'n' roll, this shift of values, and entanglement with political matters. But why return to recording now?

Wyatt shrugs, a little despondent. "It takes years to build up a craft, so really I had to turn back to this business 'cause I can't do anything else." He pauses, squirming in his chair and frowning again. "Getting back into rock music ... I feel it's like some strange nightmare where I'm going back to school or where I'm trying to get into the clothes I wore when I was 15. It just doesn't fit any more, it's weird."

Is this what you meant when you said recently that returning to the music biz was like a defeat?

"It isn't a defeat 'cause I'm still alive. But I'm surprised I'm doing it again. I thought I was going somewhere else — I don't know where, honestly — it'd be interesting to know, if I weren't in this chair, where I would be...

"I tried at the Labour Exchange for a job. The only job they had was painting chess pieces just down the road and Alfie and her mum said 'You can't do that, you're selling yourself short, you're a musician'. I think really I've been made to feel guilty about not doing it. But I've got to earn a living and, like, that's my job."

ONE RESULT of Wyatt's search for a more politically effective mode of action than rock music was his joining the Communist Party some two years ago. While he's willing to talk about it, he requests — for

'fear he'll be accused of preaching — that I make clear I asked him to. So why did you join, Robert?

"Well, the reason today I think I joined is... er... fundamentally I think most of our troubles are caused by the institutionalised unaccountability of the major Western capitalist countries and their expansion and their appropriation of the resources of a large part of the world for their own benefit. And, er, to justify capital's growth at the expense of Namibian mineworkers or whoever, the people in power rely on a particular bit of myth, of mystification, which is a notion I call the 'divine right of the few' — the idea that it's right, it's nature's way, for certain people to have and others not to have.

"The notion of this 'divine few' should strike a bell with everybody who's ever had to deal with the fact that they're not a genius, or male, or white, but it's called lots of things — "maintaining standards', 'law and order', anything to hide the fact that this divine deserving elite actually give themselves the right to preserve and expand themselves at the expense of others.

"And ... er... the history of Communism seems to me the history of the attempt to expose that hypocrisy."

Typically, after this thumbnail critique of capitalism and trashing every other left-wing grouping in the country, Wyatt admits to a little uncertainty.

"I have doubts at times, like Afghanistan, but then I look at all the people who've been anti-Communist — Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Pinochet, Nixon, Thatcher, Botha — and I think, well, Communists must be doing something right."

Well, maybe. The pity of it is that Wyatt feels his enthusiasms for politics and music to be not a fruitful tension but at an absolute impasse. And his fear that the politics will — to simplify drastically — somehow taint the music in the eyes of his audience can lead him into a defensiveness that is almost comic, as when he explains the choice of Ivor Cutler's 'Go And Sit Upon The Grass' as one of his future singles.

"I like it because it pokes fun at people like me. It says 'do not mind if I thump you when I am talking to you, I have something important to say'."

You see your songs as thumping people?! ask, incredulous.

Wyatt ponders. "Well, I like to poke fun at myself because there's this awful thing that seems to happen if you talk about anything other than music and 'fun'... the danger is you'll into a sort of left-wing Cliff Richard.

"And that," laughs Robert as he wheels off into some left-wing shadows, "is an appalling thought to have hanging over your head."

|

|