Charles Hayward was something of a musical maverick. In later years he served time with a diverse number of groups such as High Tide, Radar Favourites, Gong and This Heat. The latter had a degree of critical acclaim and produced a number of well received albums in the late 70s and early 80s. Since the demise of This Heat he seems to have ploughed his own furrow with various releases under his own name or in collaboration with a miscellany of artists on the experimental fringes.

"Charlie had originally been asked to join the group because he had a magnificent red Premier Keith Moon style kit, with the two bass drums, extra toms etc. The fact that he could play was a bonus, his parents had paid for lessons over a number of years and he was technically brilliant. After a while he said we could rehearse at his house, a huge Victorian place across the road from Camberwell School of art. This became a regular thing two or three times a week and went on through the final year at school and beyond. Eventually we felt we needed a change of direction, we were writing more instrumental stuff for which we needed keyboards and sax, plus a new bass player. We soon found a sax player, and then Dave Jarrett came in on keyboards. He had also been at Dulwich College and was very much a Mike Ratledge clone. Still we couldn't find a suitable bass player, we had the instrument but nobody to play it. In order to rehearse I said I'd learn the parts and fill in until we found a permanent replacement. We carried on this way until I realised I quite enjoyed it, and the others thought I was doing a good job, so quite by accident I filled Hie vacancy. The sax player had left by this time and we were down to the basic four piece which became Quiet Sun.".

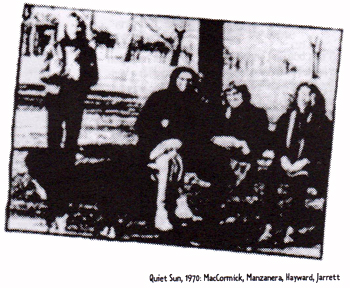

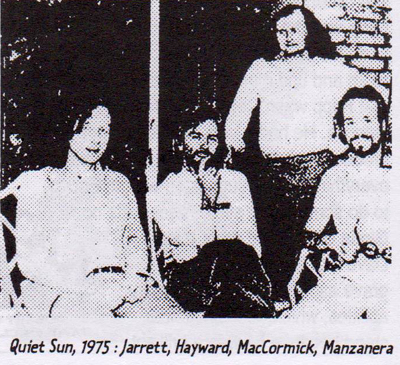

Quiet Sun were very much a musicians band, unusual chord sequences and time signatures, with vocals playing a diminishing role in the increasingly sophisticated music. Bill MacCormick is modest about his own musical abilities, to pick up the bass guitar from scratch and within a few months be playing such complex arrangements is impressive indeed. The name Quiet Sun had come into being sometime in 1970 after Ian MacCormick had come across a magazine article about sunspot activity entitled The Years of the Quiet Sun.

"Warner Brothers had a small studio somewhere in Dorset where we spent a few days recording demos. We organised a few gigs around West Norwood for a fairly loyal following mostly of people who had known us from school, and occasionally played other places. I particularly remember a shambolic appearance on Worthing Pier supporting Steamhammer, but live dates were pretty few and far between. In the end Warner Brothers decided not to sign us. We were probably a bit too obscure to have any real chance of getting a recording deal."

As the momentum within Quiet Sun began to fade other avenues began to open for individual members. Guitarist Phil Manzanera successfully auditioned for Roxy Music and Bill MacCormick joined up with Robert Wyatt's first post Soft Machine project, Matching Mole. His bass playing abilities had been noted when Quiet Sun and Gary Windo's Symbiosis shared a stage during a gig in Portsmouth.

"Quiet Sun were supporting Symbiosis, with Robert on drums that particular night. Their line up tended to be very fluid and depended on who was available. Towards the end of their set we were asked to go up and jam, it was the first time Robert had actually seen me play. Life for him in Soft Machine had become pretty awful, he was very depressed. They treated him very badly, he gave that band some humanity. Mike Ratledge in particular wrote technically fantastic stuff that I enjoyed listening to, but Robert wrote the good songs."

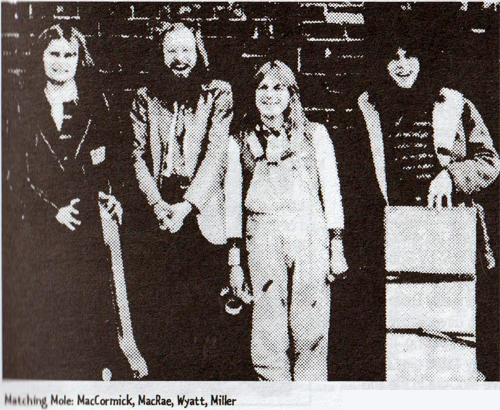

The inevitable Wyatt / Soft Machine split finally occurred during the Summer of 1971. Ian MacDonald (nee MacCormick) summed it up nicely in a 1975 NME retrospective, "With him he took most of the group's humour and a large slab of their profundity too." In late 1971 Robert began to sound out musicians for what would become Matching Mole. Bill MacCormick was first to be approached, Dave Sinclair (keyboards) had recently split from Caravan, and Phil Miller (guitar) was available after the demise of the short lived DC and the MBs, which had included his brother Steve, Lol Coxhill and Laurie Allan.

"In September 1971 Robert asked me if I would be interested in getting a band together. A couple of months later, with Dave Sinclair and Phil Miller on board, rehearsals began at a house in Notting Hill. We tried out Moon in June, some of Dave's longer Caravan pieces and few new ideas. As it turned out much of the album was improvised and some of it recorded completely solo by Robert. It was rather thrown together really, certainly not what CBS were expecting. Eventually Dave Sinclair was eased out, he was never entirely happy with the way we were progressing. It was a bit too free for him. We did play some gigs with both Dave Sinclair and Dave McCrae in the line up, mainly in Belgium and Holland, but it wasn't really working with two keyboard players. Money was one of our main problems though. I'd had a job for a while the previous year and at one point I actually ended up paying the other members of the band."

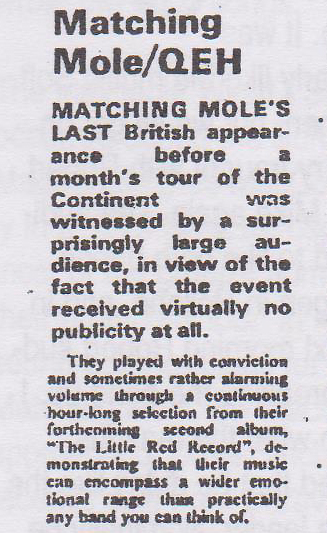

Recorded under difficult circumstances due to power cuts (miners' strike) and bargain basement technology, the first Matching Mole album is a bit of an acquired taste, but on repeated listening many of the less immediate parts reveal hidden depths. Unwary listeners can be lulled into a false sense of security by the opening track Oh Caroline, a poignant song with a beautiful melody, apparently about a recently ended relationship with journalist Caroline Coon, and probably Robert Wyatt's best known song. After the wordless multi tracked vocals of Instant Pussy and the tongue in cheek Signed Curtain the rest of the album is mainly group improvisations over a few basic chord structures, plus a couple of solo Wyatt mellotron pieces. How would this translate to the live situation? Quite successfully in some quarters it would seem. Soft Machine had always been more popular in mainland Europe, and so it was with Matching Mole.

"In the UK we were paid very poorly for our live performances, whereas in Holland, Belgium or France it was far better. In those countries it was a different sort of audience, particularly in France, much more arty. We always went down well in Amsterdam, especially the Paradiso Club where we played on a number of occasions. Our set at that time included bits and pieces from Soft Machine numbers, borrowing Hugh Hopper chord sequences and various other things. It was a very enjoyable period."

Around this time, with the ever improving Phil Manzanera in their ranks, Roxy Music were beginning to attract attention, but their lifelong problems with bass players were about to begin.

"One of the first breaks Roxy got, apart from a rather over the top review of their demos by Richard Williams in the Melody Maker, was at a big festival somewhere in Lincolnshire in May 72. They'd recorded the first album and this was to be their first high profile live appearance after the sessions, but with about a week to go bass player Graham Simpson had a nervous breakdown. Apparently they phoned me but I was in Paris with Matching Mole. That was that, I was in wrong place at the wrong time, but who knows? With their track record with bass players I might have only lasted a couple of weeks."

Meanwhile back in the real world, Matching Mole were writing and recording. Studio time for the second Matching Mole album was booked for August 1972.

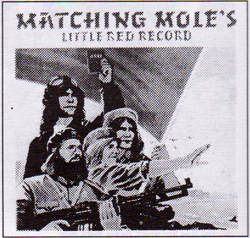

"At my suggestion we hired Robert Fripp to produce what became the Little Red Record. A very nice man, but as it turned out totally wrong for the job. Unfortunately he terrified Phil Miller, to whom Fripp was the ultimate guitar player. Phil would try to do his parts with Fripp watching from the control room and find it most intimidating. It has to be said that Fripp wasn't terribly helpful under the circumstances. He had a very dictatorial approach to his production duties, he insisted on the final say in everything. I also suggested we get Eno in to do some of the synthesiser parts on Gloria Gloom and other things. Dave McCrae took this as a grave aspersion on his keyboard abilities, which I couldn't understand because he was a brilliant electric piano player but hadn't as far as I knew used synthesisers."

|

|

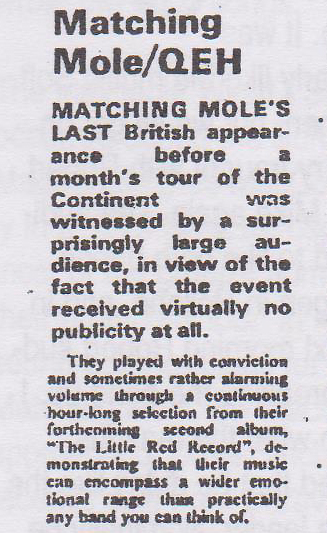

Matching Mole's Little Red Record came out in September 1972 to good reviews, helped along by Ian MacDonald who was by now assistant editor at the NME. Live reviews had also been favourable.

"After the album sessions finished we toured Belgium and Holland with Soft Machine, the Jenkins / Marshall / Hopper / Ratledge line up. It was a nice tour, I didn't particularly like the music Soft Machine were producing then, but we all got on well. It could have been very fraught with Robert meeting up with Hugh and Mike again. The audiences listened and seemed to like both bands. The last gig was in Groningen in Holland, and in the hotel restaurant the next morning Robert suddenly announced he was breaking the band up. I was never really sure as to what the reasons were. It has been suggested that he didn't like the responsibilities of being the leader. Nominally he was the leader, but if you look at the credits for the music it was actually spreading out amongst the rest of us. We were all writing and it seemed to me that we were developing a sound. Whereas the first album had been very much improvised around some very simple riffs, the second album had a greater structure to it. We were also beginning to make some headway in mainland Europe. We were playing festivals and getting good billing with money up front, we could play any major French/Dutch/Belgian city or town and pull a

decent sized audience. I couldn't quite see what Robert's problem was, perhaps he just didn't like the music and was too polite to say. The rest of us were absolutely flabbergasted, it really didn't seem to us to be a reasonable or sensible thing to do."

|

|

In the Autumn of 1972 a phone call from Robert Wyatt began a little known chapter in the history of the Planet Gong.

"Robert phoned me to say that Gong were looking for a new bass player and were auditioning at the Manor, Richard Branson's studio. I wasn't too sure about it but went along anyway, and a few days later I got a call asking me if I wanted to join them in France. So I picked up my guitar, flew off to Paris and was taken to this hunting lodge somewhere in the countryside. This would be around November and it was

bloody cold. At the time the line up included Daevid .Allen, Didier Malherbe (sax), another Frenchman on guitar (probably Christian Tritsch, recently switched from bass), and a drummer whose identity escapes me (probably Laurie Allan). The band were essentially French, Daevid Allen and Gilli Smyth were both fluent in French, so that was the common language. The only opportunity for me to communicate effectively was through the music. I began to resent the fact that I was there, I had nothing with me apart from the clothes I stood up in, I couldn't sleep because it was too cold, I spoke very little French, and nobody seemed to be going out of their way to communicate with me. Some of the sessions got a bit weird, Daevid seemed to go out of his way to give some sort of competitive edge to the situation. We'd be on opposite sides of the rehearsal room sort of eyeing each other, perhaps this was part of his creative process. It was very strange, I don't know why it happened that way at all. It might have worked if I could have sustained it because there were definitely sparks flying, Didier was enjoying himself tremendously. After four or five days though I told them I just couldn't handle it. So that was that, and they drove me back to Paris."

Since the break up of Matching Mole Mk1 Robert Wyatt's musical activities had been restricted to a few guest appearances, but early 1973 found Bill MacCormick cajoling him to reboot his own musical direction.

"Robert had gone off to Venice with Alfie (Alfreda Benge, whom he later married), she was working in some sort of editorial capacity on the Nick Roeg movie Don't Look Now. While he was there we communicated on a fairly regular basis and I suggested various musical projects. Through his connections I met up with Francis Monkman and Gary Windo, and eventually Robert agreed to Matching Mole Mk2. Whilst he'd been away in Venice he'd been writing some stuff on a portable keyboard, quite a lot of which ended up on Rock Bottom."

Francis Monkman (keyboards) had been a founder member of Curved Air playing on their first three albums, finally quitting in 1972. Since then he has worked mainly as a session man, although he did spend a number of years as a member of Sky with classical guitarist John Williams. Gary Windo was a larger than life character who had his roots in jazz, but who would frequently cross musical boundaries if the spirit and attitude were right. His rasping tenor sax tones added that extra ingredient on countless recordings, particularly Robert Wyatt's Rock Bottom and Ruth is Stranger than Richard. His sudden death in 1992 was a great loss.

"We started rehearsing, although I use the term very loosely, it was in fact a couple of afternoons up at Alfie's flat. I do remember one day Robert and I went across the road to a pub where they had a band, and we ended up playing rock 'n roll songs. Given my background these were things I'd never played before, so it was quite interesting trying to work out the bass parts that every bass player in the world knew as standards. I'd just never got round to it. My bass playing had all come from playing written parts for Quiet Sun songs. Then Gary and I did a couple of pubs gigs with a pick up band including John Halsey and Ollie Halsall from Patto. We were stopped by the landlord at one of the gigs, it wasn't what he was expecting."

The thought of an unsuspecting publican being confronted by the uncompromising blowing of Gary Windo is one to savour. Jumping ahead a year or two, Bill MacCormick was also involved in the sessions for Gary's Steam Radio Tapes.

"He certainly was the wild man of the sax, a great player, lots of enthusiasm, when I heard he'd died it was a great shock. In April 1976 I played on the sessions for his Steam Radio Tapes. It started at his flat in Hampstead, quite a lot of it was working on songs that Pam his wife had written. We actually put a band together which played one gig, at Maidstone College of Art. We had Nick Mason on drums, a guitarist whose name escapes me (possibly Richard Brunton), and Pam playing piano and singing. From that it evolved into the Steam Radio Tapes down at Britannia Row studios. Myself and Hugh Hopper played bass, often both of us on the same number, it's virtually impossible to tell who is playing what."

Meanwhile back in 1973 the Matching Mole revival gathered pace, but ended abruptly when an intoxicated Robert Wyatt fell out of a window at a party and sustained severe spinal injuries, resulting in permanent confinement to a wheelchair.

"I think the announcement had gone out in Melody Maker saying that Matching Mole Mk2 were ready to go and were currently rehearsing. Then it all came to an end with the accident. Robert had seemed enthusiastic about the new line up, admittedly I'd badgered him into it. It was a great shame because quite a lot of Rock Bottom had already been written, and when I heard the album I thought if things had been different it could have been us. The accident happened on a Saturday night and I found out on the Sunday, by the evening I was in hospital with appendicitis. The doctor said it could be brought on by stress, or a sudden shock. After the operation I did very little for several months apart from regular visits to Robert at Stoke Mandeville Hospital. He was fortunate in that people rallied round after the accident, Pink Floyd arranged a benefit. When he came out of hospital I was a frequent visitor at his and Alfie's flat, I was amazed how cheerful he was. I did a few sessions for Eno's Here Come the Warm Jets album in September 73, appearing on a couple of tracks, but basically I stopped playing for about 18 months."

|

This musically inactive period was very active in other areas and set the tone for a future career.

"I joined the Liberal Party in December 73 and became heavily involved in the General Elections of February 74, and in May that year I stood in the Council Elections. I had also wanted to go to university to read politics, but having obtained the necessary qualifications I turned down offers from the London School of Economics and Warwick University in favour of reviving my musical career. Phil Manzanera had come up with the idea for the Quiet Sun album in late 74 and in the end there was no contest."

Phil Manzanera released four excellent song based albums during periods of Roxy Music inactivity in the mid 70s. They were Diamond Head (1975), 801 Live (1976), Listen Now (1977) and K-Scope (1978). Bill MacCormick was bass player on most of the sessions and a major contributor to the writing. The two later albums also contained a significant input from Ian MacCormick. Late 1974 saw the beginning of the sessions for Diamond Head, and running parallel was the recording of Mainstream by the temporarily reformed Quiet Sun. Was Quiet Sun's one and only appearance on vinyl a true representation of their sound?

"Yes, there wasn't time for anything fancy as it was entirely recorded during Phil's sessions. He'd book the studio for say 12 hours, then do 8 hours of his stuff and then 4 hours of Quiet Sun, usually after midnight. There was a certain amount of overlap between the two projects, a number of tracks on Diamond Head were fragments of songs that didn't make it on to the Quiet Sun album. It was all done very quickly. Having got Dave Jarrett away from teaching mathematics or whatever it was, we'd managed to get a few days rehearsal. The production on the album was pretty minimal, apart from a few treatments by Eno. Phil knew him from Roxy of course, and I knew him from the second Matching Mole album and my sessions on his first solo album. The Quiet Sun sessions were really good, I think it probably sounds a bit off the wall because that's the way it had to be recorded, we weren't trying to make it sound pretty or anything. Phil just wanted to put it out because it made sense of the couple of years we'd spent writing the material and getting a sound together. It was a cheap album to make and I'm still getting royalties from it."

Robert Wyatt's post accident career had started well with his highly acclaimed Rock Bottom in 1974, and Ruth is Stranger than Richard the following year. The sessions took place during May 1975 at the Manor in Oxfordshire and featured an interesting mix of musicians.

The Manor was a very nice place to record, the guys in the studio were great, the food was good. It wasn't technically outstanding, but the engineers got an excellent sound and were prepared to try anything. It was nice to work with Robert again. I suspect he felt a bit taken over at times on those sessions, there were some very forceful personalities around, but it was a great two or three weeks. It was quite funny really, there was an underlying tension between the jazzers like George Khan and Gary Windo, and some of the rockers. Basically Brian Eno thought jazz was crap, whereas they couldn't quite understand what this rather bizarre looking character was doing in the studio. But it worked really well and I really enjoyed it. There are a few things on that album where I felt I played particularly well, Team Spirit was one, Five Black Notes and One White Note was another."

|

|

The next Manzanera project culminated in the 801 Live album. A varied selection of original material was complemented by carefully chosen covers, in particular an outstanding version of Lennon and McCartney's Tomorrow Never Knows.

"801 came together during 1976, and sprang out of sessions that eventually ended up as the Listen Now album. The sessions had been going on for a long time because of Phil's commitments with Roxy. Eventually he decided he wanted to do something in the summer, and suggested getting a band together and playing some festivals."

In addition to Manzanera and MacCormick the short lived 801 Mk1 also included Brian Eno (synth/vocals), Simon Phillips (drums), Francis Monkman (keyboards) and Lloyd Watson (slide guitar/vocals).

"Lloyd Watson was a singer songwriter who had been support on one of the early Roxy Music tours. It was an interesting combination, a slide guitar player and Brian Eno. As we all had a free summer we were able to get it together in the country. We had the use of a house near Ludlow in Herefordshire so we spent a few days down there examining the possibilities. We looked at songs from Phil's albums, Eno's albums, some Quiet Sun stuff plus a few cover versions. I'm sure the others will claim otherwise but it was my idea to do Tomorrow Never Knows, but I think the idea of doing the Kinks' You Really Got Me just came out of jamming around. We had further rehearsals and were then supposed to go off and do a series of festivals in France, for which we would be pretty well paid. About two weeks before the first event at Orange in the south of France, there was a riot at another festival which resulted in Giscard D'Estaing cancelling all similar events in France that summer. As you can imagine this was a bit of a blow, we could see all this money we'd been expecting to earn going down the tubes. To compensate Phil suggested we make a record, so our final gig at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London was recorded by the Island Mobile and this became the imaginatively titled 801 Live. The album was incredibly cheap to produce, it still sells and the royalty cheques still come in. We had previously played the Reading Festival and on the day it had been raining so hard that the audience area had become a sea of mud, you could see the steam rising off the crowd. As we hit the stage the sun came out. It was a wonderful moment, and more steam rose from the bedraggled masses. It was a great set, we really played well and thoroughly enjoyed ourselves."

About a year later there was a British tour under the 801 banner to promote the new studio album Listen Now.

"It was a lively tour, along with Phil and

myself, we had Paul Thompson (drums), Dave Skinner (keyboards) and Simon Ainley (guitar/vocals). The whole 801 project was a good outlet for songs that Phil, Ian (MacCormick) and myself had put together. We would go over to Phil's house and spend days working on various new ideas. Listen Now came out of a lot of half finished things that Phil had, to which Ian and I added lyrics and melodies. It took a long time to record, December 75 through to July 77, and featured a cast of thousands. Simon Ainley did all the lead vocals, amongst the other musicians were Simon Phillips, Dave Mattacks, Mel Collins, Eno, Francis Monkman and Eddie Jobson. Around this time I also had a brief foray into journalism. I did a few things for the NME, the first one about football hooliganism, then an interview with Julie Christie about her anti nuclear stance, and finally a look at the unwelcome rise of the National Front. The latter piece caused a few problems when I received a death threat, which had Special Branch crawling all over the place for a while. These sort of issues were reflected in the lyrics on Listen Now, it was an unpleasant and threatening time in this country, it seemed like we were moving towards a totalitarian state. I did a couple of things from America for Streetlife magazine, interviewing Warren Beatty about his political activities, and covering the 1976 Presidential Elections."

K-Scope, the last in the quartet of Manzanera albums, was recorded and released in 1978. Writing credits once again, apart from lyrics by John Wetton on one track, were all Manzanera / W.MacCormick / I.MacCormick in various combinations.

|

|

" K-Scope had no political concept and was musically a much less coherent piece of work than Listen Now, although recorded in a shorter period of time at Chris Squire's studio. Tim Finn did most the lead vocals, with his brother Neil helping out on keyboards. Their band Split Enz, whom Phil had been instrumental in bringing over from New Zealand, had just split up. Neil and Tim of course later found fame and fortune as Crowded House. It was very co-operative throughout the sessions and overdubs, then Phil rushed off and mixed the whole thing very quickly. I had nothing to do with the final mix at all, and when the album was released it didn't really come up to my expectations. The reason for the haste, it later emerged, was that Roxy were reforming so Phil was keen to get everything else out of the way."

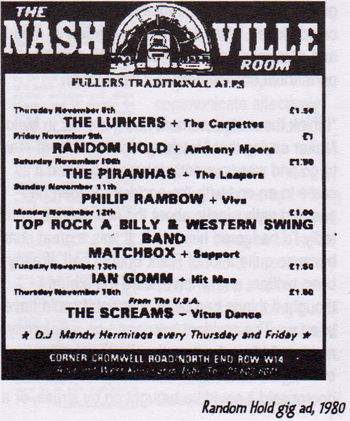

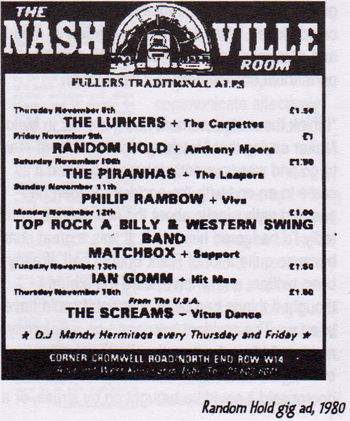

The final chapter in the Bill MacCormick musical career began in late 1978. Random Hold were formed by David Ferguson (keyboards) and David Rhodes (guitar). The sound they evolved was dark and occasionally austere yet always capable of moments of high drama and excitement, sometimes bringing to mind the aggressive metallic sound of mid 70s King Crimson, but in a more song orientated format.

"I'd watched them play and thought they were quite interesting, so I put some money in and was later invited to join, along with Simon Ainley (guitar / vocals) and Dave Leach (drums). We struggled

for some time to get any interest, but eventually I was able to exploit some of my contacts in the music business, in particular Alan Jones at the Melody Maker. After seeing us rehearse for about half an hour he was convinced we were the next big thing, and gave us a spread in Melody Maker which certainly had a dramatic effect on the record companies. Having been in a situation where nobody was interested, we suddenly found ourselves in an auction between three record labels. We successfully played them off against each other and ended up with a substantial advance of 80000 from Polydor, which we immediately blew on expensive guitars and other such luxuries."

So far so good, but there were storm clouds gathering.

"Simon Ainley wanted to be a rock 'n roll star, lots of chicks, lots of guitars on the wall and as big a bank balance as possible. But Rhodes and Ferguson were artists, serious people with serious objectives in life, they wanted to do something deep and meaningful. Without any reference to me they decided to fire him. This was an error of judgement because they lost a good front man, without him the whole image became one of too much shade and not enough light. Simon was a fairly easy going individual and it reflected in his contribution to the band, it lightened what at times was rather gloomy music. His singing was good, but his guitar playing was too lightweight for Ferguson and Rhodes. Personally I felt it gave counterpoint to the rather dour Rhodes approach, a brilliant technician but rather introverted. Around the same time drummer Dave Leach's medical problems were used as an excuse to oust him in favour of Peter Phipps whose claim to fame was that he used to be in the Glitterband! Polydor were unhappy about Simon's departure and they were never too keen after that."

Despite the personnel upheavals there was interest from an unexpected quarter.

"We discovered Peter Gabriel was something of a fan. I don't know how he found out about us but he came along to the Rock Garden to see us. He persuaded his manager Gail Colson to sign us up for a management deal, and she had us go down to Gabriel's place and work with him on his new material. We spent a couple of weeks down in Bath working on the songs and structures that became his third album. We didn't actually play on the album itself, in the end he decided to use American supersessioners. Gabriel had wanted to produce our records, but his own heavy schedule at the time got in the way of that.

|

Instead we ended up with Peter Hammil who was part of the same management stable, a very nice guy but not right for us. After three rather undisciplined weeks in the studio the tapes were ready for mixing, it was then that we realised just how dictatorial Mr.Hammil was. We had no say in the mix at all, we used to sit there and get more and more pissed off, eventually I stopped going. When The View From Here album came out I found the sound a bit thin in places, but aside from the production I don't think we performed well in the studio. The demos we did for Polydor with the original line up and produced ourselves were infinitely superior."

I caught them live in a one off gig at Oxford Polytechnic in February 79 with the original five piece line up, and they were brilliant.

"We toured England with XTC, and then again supporting Peter Gabriel. The Gabriel tour then moved on to the States where our album had been released. We were doing well, sufficiently well for our American label to set up a number of club gigs at the end of the tour. But then everything all fell apart. It had been a bit fraught for some time, with Dave Ferguson and I having major political disagreements. Towards the end of the American tour we had a few more serious clashes, and when we got back the two Daves decided they wanted to carry on without me. They had unfortunately forgotten that the band owed me rather a lot of money, so when I called in the debt it effectively killed the band. By this time I was fed up with the whole business so I just dropped out completely, the end of my music career. Been there, done that!"

What of Rhodes and Ferguson?

"Dave Rhodes was a great songwriter, and despite all the animosity I helped him produce some demos immediately after the band broke up, but eventually he seemed more comfortable as a backing musician on Gabriel's projects. Dave Ferguson went onto a successful career in TV theme and incidental music. I haven't seen either of them for some years. Random Hold hardly sold any records, and I've long stopped receiving royalty statements, which were laughable anyway."

Despite Bill MacCormick's misgivings about the production I can highly recommend all the Random Hold recordings. The essential items are the eponymous debut 12" EP and the album The View from Here. For completists a rerecorded version of Etceteraville from the album was released as a single, with the previously unavailable Precarious Timbers on the flip side. At the end of the day personality clashes and record company indifference ensured that Random Hold never fulfilled their undoubted potential.

The Bill MacCormick playing technique seemed unorthodox in its development, starting with the complicated time signature stuff in the early days, and ending up as a more orthodox rhythm section style.

"In Matching Mole you were effectively soloing a large part of the time, my playing was all about trying things out and taking risks. Working with Robert was always a challenge, you never knew what was going to happen next. Post Matching Mole my playing became simpler and I began to feel more relaxed as part of a rock rhythm section, as long as the material was interesting."

Bill worked for the MP Simon Hughes for a while, and then went on to become London Organiser for the Liberals, working at Party HQ until 1989. By this time he had become involved with the market research company of which he is now a director. He is currently a Liberal Democrat Councillor in South London.

Sincere thanks to Bill for being such an

interesting and co-operative interviewee,

especially after I arrived 2 hours late after a

horrendous journey through the sort of traffic

only London can produce.

Stephen Yarwood

>> Digital version of the interview on the Facelift website (slightly different from the original paper version)