| |

|

|

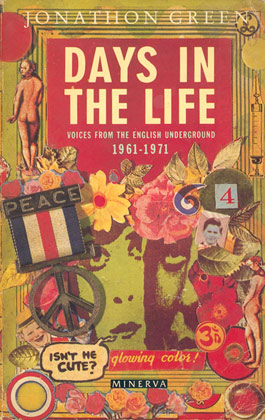

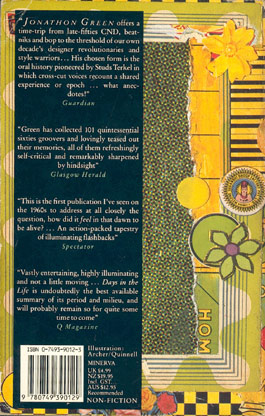

Days In The Life - Jonathon Green

Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971

Dans cet ouvrage publié en 1998 aux éditions

Minerva, Jonathon Green part à la rencontre du Londres

"underground" des 60's. Il brosse le portrait

d'une ville et d'une génération à travers

une sorte d'abécédaire kaleidoscopique et

les souvenirs d'une centaine d'activistes majeurs de cette

période dont Robert Wyatt...

| |

...Pendant ce temps, que se passe-t-il dans cette

Angleterre, justement? (...) Dans le courant de cette

nouvelle culture, Marc Boyle présente un light show

en compagnie d'un groupe nouvellement formé, de retour

des Baléares où ils ont pas mal expérimenté ce genre

de choses (c.à.d. de fameuses substances):

Soft Machine. De leur côté, des gens comme Miles,

Jack Henry Moore, Jim Haynes, créent un certain nombre

d'entreprises formant petit à petit le noyau d'un

underground vivant, avec des magazines, un hebdo (International

Times), et surtout, un endroit sur Southampton Row

appelé à devenir l'épicentre de toute une révolution

en Grande-Bretagne : UFO. C'est un sous-sol d'assez

bonnes dimensions, où l'on peut faire un peu de tout:

projections des films de Jack-Henry Moore et Yoko

Ono, diapositives organiques de Marc Boyle sur des

corps féminins en mouvement, et bien sûr, beaucoup

de musique. Trois groupes s'y illustrent régulièrement:

le Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band de Vivian Stanshall, et

Neil Innes, héritiers à l'anglaise des Village Fugs

de New York; le Soft Machine, première mouture; et

Pink Floyd...

Alain Dister - ROCK CRITIC Chroniques de rock'n'roll

(1967-1982)

|

|

Robert Wyatt words about...

Jazz Jazz

It all started for me in the

50s when I was a jazz fan. I still am. That was my underground.

That was the life I discovered outside the prescribed life.

I was born in 1945, left school in 1960. I hadn't got enough

exam results to get any particular job so I worked in lots

of things. The place where culture and politics seemed to

meet for me was always centred around black music. Jazz

in the 50s. That's the romantic period for me. To me protest

music was Max Roach, Sonny Rollins and Charlie Mingus. I

didn't understand folk music, I didn't even like the songs

at the Aldermaston march. I knew about jazz, I wasn't particularly

well read, but I knew the sleevenotes of about twenty LPs

backwards and could spot a new bass player on the New York

scene as quick as anybody.

Mods:

'Something very sharp'

The big difference between the trad

jazz people and the modern jazz people, which is where the

word 'mod' really comes from - the modernists who went

to modern jazz gigs - was that the mod thing tended to be

more working class or East End lewish, whereas the trad

thing tended to be public school dropouts - much more English,

people leaping up and down to trad jazz, already the thing

of being ostentatious in dress, whereas the modernist thing

was very much not ostentatious. Somebody else might notice

how you had your tie, someone who knew about things like

that, but it wasn't ostentatious. But we did want to function

as a parallel world. Mods:

'Something very sharp'

The big difference between the trad

jazz people and the modern jazz people, which is where the

word 'mod' really comes from - the modernists who went

to modern jazz gigs - was that the mod thing tended to be

more working class or East End lewish, whereas the trad

thing tended to be public school dropouts - much more English,

people leaping up and down to trad jazz, already the thing

of being ostentatious in dress, whereas the modernist thing

was very much not ostentatious. Somebody else might notice

how you had your tie, someone who knew about things like

that, but it wasn't ostentatious. But we did want to function

as a parallel world.

Light-shows:

'You had to have things going "Pow!"'

Mark Boyle was burning himself to

pieces doing these experiments with different coloured acids.

You just saw him with these goggles, looking alI burnt and

stuff, high up on some rigging. He used to play tricks,

he used to make bubbles corne out of people's flies and

things. You couldn't see exactly what he was doing from

on stage, but the atmosphere was good. Light-shows:

'You had to have things going "Pow!"'

Mark Boyle was burning himself to

pieces doing these experiments with different coloured acids.

You just saw him with these goggles, looking alI burnt and

stuff, high up on some rigging. He used to play tricks,

he used to make bubbles corne out of people's flies and

things. You couldn't see exactly what he was doing from

on stage, but the atmosphere was good.

The Floyd always had their own lights people, but no one

else did and Mark used to do the place, not particularly

the groups, but the walls, everything. The light-shows meant

that what we shared with the Floyd was that as personalities

you could hide and the overall group effect could be more

important th an the individuals. The normal thing would

be that there would be a focus on one or two individual

performers, even in the R&B bands, the lead guitarists

would get that focus. Whereas we and the Floyd would hardly

be recognised off stage, nobody knew what they looked like

through the light-show. The anonymity of light-shows was

nice - the fact that you were almost in the same swirly

gloom that the audience were in was relaxing and you could

get a nice atmosphere going.

The

Deviants : 'The Worst record in the history of man' The

Deviants : 'The Worst record in the history of man'

I didn't know MickFarren well

and I don't think he particularly welcomed what he thought

we [the Soft Machine] represented. But I certainly admire

him because he was a sort of protopunk and saw elements

immediately that were false. He heard the false notes being

rung all around him at a time when people thought it was

all in tune.

The

14-Hour Technicolor Dream: 'Everybody I'd ever known swam

before my eyes' The

14-Hour Technicolor Dream: 'Everybody I'd ever known swam

before my eyes'

I got a short-back-and-sides

haircut and a suit and tie to do that gig. That was my avant-garde

gesture. The Floyd had those pyramids as far as I recall.

They were doing very slow tunes.

The

Pink Floyd: 'What we wanted was an avant-garde pop group' The

Pink Floyd: 'What we wanted was an avant-garde pop group'

The Pink Floyd were with a

lovely bunch of people, Blackhill, and they were very nice

and I think they were an honourable exception to the shady

rule about managers. I think they were nice people and really

cared about the people they worked for. I think that most

of were less lucky than that.

The

Soft Machine: 'The only other bloke In Kent with long halr' The

Soft Machine: 'The only other bloke In Kent with long halr'

In Canterbury I got into a

local sort of beat group, the Wild Flowers. The name had

nothing to do with flower power; we lived in the country

and Hugh Hopper had a book called Wild Flowers and

I think he thought it up. Wild Flowers was the beginning

of what became the Soft Machine. Hugh Hopper's brother Brian,

who played saxophone, was a friend of Mike Ratledge and

when Mike Ratledge came back from university and wanted

to play, we were the only people there to play with. So

he joined the band, playing piano. But nobody in the band

was trying to do the same thing at alI, which is why it

was quite original and why, after a couple of years, it

fell apart. It was a constant process of disintegration

really, getting in new people to fill the gaps. Which in

the 60s was rare, because most bands were quite stable.

I talked to Nick Mason of the Pink Floyd about that once.

I said, 'How come you lot have stayed together so long?'

and he said, 'We haven't finished with each other yet.'

But it kept changing, we kept on tinkering with it and tinkering

with it and throwing each other out of it and leaving it

until eventually alI the kinks were ironed out of it and

in the end it became a standard British jazz-rock band.

I don't know what happened in the end. I stopped listening

after a while - I stopped listening before I even left.

When we came up to London there were two connections: Daevid

Allen had the connection with people like Hoppy. The other

connection was Kevin Ayers, who played bass guitar and wrote

songs. He was the only other bloke in Kent with long hair.

The name Soft Machine came through Mike Ratledge. He had

books like V and alI that kind of thing. I knew the

name was taken from Burroughs but I don't think it intrigued

me enough to get a copy. Wild Flowers more or less became

the Soft Machine. We trickled up to London and then regrouped,

one by one.

Kevin Ayers was important in that he knew the AnimaIs office,

where Hilton Valentine and Chas Chandler were already starting

to manage, and they signed us up really on the basis of

Kevin's songs. They were looking for something commercial.

Chas was always looking for Slade, and eventually he found

them, meanwhile he had to put up with people like us and

Jimi Hendrix. Shortly after we joined Chandler Hendrix came

to London and musically that was tremendously important

for lots of people. For me too, if for nothing else than

that what he let Mitch Mitchell do on drums gave me space

for what I wanted to do on drums. We were using a lot of

jazz ideas on drum kits that there hadn't been room for

in the constricted time-keeping stuff I'd been doing before.

Of course this was quite the opposite of what Nick Mason

was doing with the Floyd: he was a kind of ticking clock

there - which is just what they needed. For electronic rock

his approach was more suitable - uncluttered. People like

me and Mitch were probably too busy, but at the time it

seemed exciting. So Kevin actually got us a deal and turned

us into a group that had a manager and so on. He liked bossanova

and calypso. Ray Davies and the Kinks, who started using

stuff like that quite early on, were a big influence on

him. One record company bloke told us, 'I don't know whether

you're our worst-selling rock group or our bestselling jazz

group.'

The

Speakeasy: 'There was a good deal of excess' The

Speakeasy: 'There was a good deal of excess'

The Speakeasy was exactly

the kind of place that I saw as really unpleasant. There

was a sense in me that while I was flourishing as a member

of the late-60s culture, this very thing that was flourishing

was squashing something that I felt was really more oppressed.

Rock groups meeting in expensive clubs that are difficult

to get into... what's all that crap? It was exciting and

it was interesting, there were lots of new scenes, but it's

very very hard to think it as underground.

UFO UFO

When you arrived at UFO, early

on, they were usually playing Monteverdi or something. I

was probably more awestruck by the place than most of the

punters, who I felt took it for granted.

It wasn't any easier playing UFO than the circuit, but the

demands our own. We were able to develop our own idiosyncrasies.

Our management had immediately put us on the road on a circuit

where you had to play for dance audiences. We weren't very

good at that. So the great thing for us about UFO was that

the audiences weren't demanding in the same way. They were

sitting about, most of them were asleep as far as I could

see. The very things that were our faults on the regular

circuit - that of alI the bands playing 'Midnight Hour'

or 'Knock on Wood' on any particular evening we would play

it worst, if we played it at all- became bonuses at UFO.

We couldn't play that stuff, or if we did people didn't

realise that was what we were playing.

Conclusion:

'Some kind of golden age' Conclusion:

'Some kind of golden age'

I think in the end that by

not beating the system we strengthened it. In the end the

culture we were involved in was an Anglo-american cultural

narcissism revamped, and if you look at it from the point

of view of world culture it actually reflected the power

structure, the extraordinary media power of the English-speaking

West. With the best will in the world the people involved

might have thought that they were providing an alternative,

but they were simply making the Establishment more flexible.

So I'm not at all surprised that we have proceeded to vote

in lots of incredibly right-wing and chauvinistic governments.

I don't see that as a reaction to the 60s, but as a direct

result. What a pathetic thing to think: that you can just

blow the castles down.

|